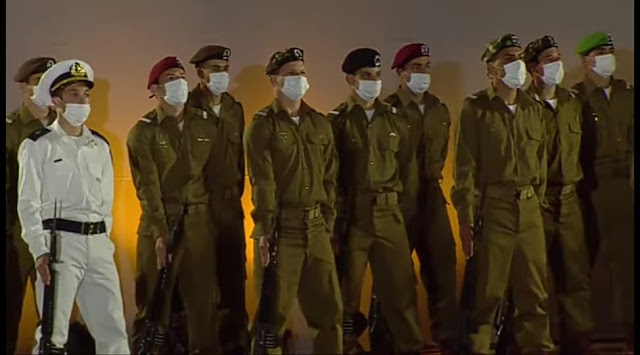

You can’t see him in the photo below, but he’s there. Right behind

the guy with the Israeli flag. My son, my baby, the youngest of 12,

representing his IDF battalion as part of an honor guard to welcome Lloyd

Austin, the United States Secretary of Defense, on his first visit to Israel.

I watched the livestream and for a moment I thought: there’s the tip of his boot! Seconds later I thought I caught a glimpse of his back. But you know, it didn’t matter whether or not I could actually see him. I got Jewish nachat* just knowing he was there, my baby, standing tall and straight and proud.

Like all my children, Asher is a dual citizen of both the

United States and Israel and somehow that made it all the more thrilling to

know he was there (even if I couldn’t see him). As the IDF band played first

the American and then the Israeli anthems, I hoped my parents were watching from

the heavens. No one knows these things, but that doesn’t stop us from hoping.

I hoped my parents were proud of Asher, proud they had a

grandchild in this honor guard, a soldier in the IDF, greeting a US dignitary.

I hoped they were proud I’d ended up in Israel, that I had raised a beautiful family in the Holy Land.

It had been a long road here, to this place.

When I first arrived in Israel, I felt I belonged nowhere. I

didn’t speak the language well, I didn’t understand the cultural norms of Israeli society. It took

a couple of years before I could successfully push my way through a pushing, shoving crowd and onto a bus—before it closed its doors and drove away from me.

People weren’t necessarily rude, but there was no concept of social distancing back then, or private space. There was a different pace here in Israel, an attitude of don’t

be a freier, a sucker, grab at life

while you can.

That feeling of not belonging hurt. I’d grown up in a close

family, with lots of siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles. Here in Israel, it

was just me and my husband and, as our family grew, our babies. I missed having

clan, people who knew me from when I was born, people who knew my grandparents

before me. I missed them especially at the holidays, or when I had a new baby.

There was no one to say: “She looks just like Grandma Elizabeth.”

Israel is all about family, but I had only the people in my

immediate environment: my husband and children. I wanted more. I wanted extended family.

For me and for my children.

I wanted to belong to something. I wanted my kids to belong

to something. I wanted to belong to Israel, to feel I was a part of things. So,

I delved into my family tree and history, knowing I had way distant relatives

in the country going back to Ottoman times. Maybe these people, or at least

their descendants, could be my family.

Getting to know my own history, learning about these family members, and the role they played in building the country did seem to make a difference in how I felt. There was a certain lift now to my shoulders as I walked the streets of Jerusalem, knowing my family had been here a long time, perhaps longer than the people to the right and left of me, waiting for a green light on the corner of Jaffa and King George.

My history was tangible. My great great grandparents are buried on the Mount of Olives.I visited the graves.

|

| The graves of my great great grandparents on the Mount of Olives, restored after 1967 |

There was the relative who was killed in the King David Hotel bombing, one of the few Jews killed in that event, Yehuda Yanowski. Yehuda clerked for the British (which appalled the cousins), did a stint in the RAF, mustered out, and then returned to marry his sweetheart. He went to the hotel to invite his old office mates to the engagement party that night. Instead, all were blown to smithereens—because the damned Brits had foolishly ignored the warning leaflets and phone calls the Etzel had graciously sent.

And there was my cousin, Itzhak Tsvi Yanovsky, an important banker.

|

| Itzhak Tsvi Yanovsky in front of the bank in Tel Aviv |

One of the cousins owned the first laundromat in Tel Aviv.

Another cousin smuggled guns into Israel for the Haganah. (She later married a general and settled in Beverly Hills).

The distant cousin I found who shared all this with me, was a professor of chemical engineering at the Haifa Technion. He had served in the Palmach and was my late mother's age, exactly.

It was all very rich, this history (no trickle down effect from the bank guy, by the way). But as much as I pored

over everything I learned about these Israelis, these distant blood relatives of mine, they never felt

quite like my own, like they belonged to me. The descendants of these people were happy to

exchange trees and correspond, but we never had the big, warm family gatherings of my fantasies.

In studying my family, of course, I had to go back to where

we had been in Europe, a shtetl then in Lithuania, now in Belarus, called

Wasiliski. The Jews called it “Vashilishok” and it was where my maternal grandfather

had been born. There was nachas—Jewish

pride—in this history, too. Many great rabbis came from Lithuania. The Lithuanian

Jews were scholarly. Study halls in Israel today, and throughout the world, are

patterned after the yeshivas of

Lithuania.

Here too, the history felt a little artificial, a little

off. How could I romanticize a place my family couldn’t wait to leave? A place

of pogroms, of death. But my desire to belong to anything in a land where I

belonged to nothing, made me cling to this history, too.

And yet: the more I learned about my personal family history

in pre-state Israel, and the shtetl we came from in Lithuania, the more I

settled in and became at home in Israel. I made a life here. Now I knew the

streets, and how to push my way onto a bus. I could banter with the salespeople

in the market and make an appointment at the medical center.

I put my studies aside. I stopped looking for cousins, dead

or alive, stopped looking at death records and graves. I pulled myself out of

the shtetl, out of Vashilishok, as my children came of age and served in the

army. And as my children grew up, tall and straight and proud, some of them having

families of their own, I realized that I had become rooted to the soil of

Israel. Not just by dint of my history and the people who came before me, but

by living my life here in this place.

Now I knew the truth, knew it in my bones. We are the past,

but more important than that, we are the here and now, and our children are our future. Jews aren’t from

Lithuania, but are B’nai Israel, sons of Israel, from Israel, and from Israel,

alone.

All this is in me, when I sing Hatikvah at a son’s

graduation from college, or hold a new grandson at a bris in a tiny synagogue

in the south. This feeling was with me, of course, as I tried and failed to see

my son in the honor guard, representing his battalion, on Lloyd Austin’s first

visit to Israel. And it was with me just a few days later on Yom HaZikaron, when

my baby was once again part of an honor guard, as part of the memorial ceremony

at the Western Wall.

I strained for a glimpse of my son, my baby. And this time I

saw him. He was there, standing at attention to give honor to those who gave

their lives for this country, for Israel.

This was a sad and tragic event, one that ties all of the Israeli people one to the other through spilled blood and treasure. With my son there, standing tall and straight and proud in the here and now—a soldier through and through—I owned the truth at last: I knew that I belonged, that I was surrounded by family, and that I’d come home for good.

*Nachat (Hebrew)

or Nachas (Yiddish), Definition: Proud

pleasure, special joy—as from the achievements of a child.

_______________________________________