George Eliot may not have been Jewish, but she understood

the Jewish hunger for the return to Zion. Mary Anne Evans, as she was

christened, cared about Jewish nationalism enough to make it the theme of her

final novel. Written a full 20 years before Theodore Herzl penned his utopian

novel Altneuland, and 40 years before

the Balfour Declaration, Daniel Deronda

ends with a Zionist bang: the eponymous hero is packed and ready to take off

for the East, where he is set on founding a homeland for his people in

Palestine.

Through most of the story, Daniel knows nothing of his Jewish

parentage. The ward of Sir Hugo Mallinger, an English gentleman, Deronda is

raised with every advantage and as such, feels uncomfortable to ask about his

origins. Mallinger has been so kind, and Deronda anyway assumes he is Sir

Hugo’s illegitimate offspring from an early fling—something that would be better

off left unsaid between them.

The 700-page book that is Daniel Deronda is not light reading and in actual fact is really

two stories. One story is a typical British romance, with a self-centered

British heroine, Gwendolen Harleth. The other is the story of a Jewish

awakening, in which a romance also takes place, in this case, featuring fictional

Jewish heroine, Mirah Lapidoth. The book is ponderous, even boring. The two

stories do not mesh well and only a dedicated reader would push through to the

end.

|

| Portrait of George Eliot by Samuel Laurence |

Many critics have written of the “Jewish half” and the “English half” of Daniel Deronda. F.R. Leavis split the novel into two in his The Great Tradition, and refers to the “good half” (the English half), and the “bad half,” (the Jewish half.) This is understandable, because the characters in the Gwendolen Harleth story are well-rounded and human, while the Jewish characters are wooden, and speak as if they stepped out of the Book of Isaiah. The reader imagines a kind of weird light in their eyes, as if they were immortal Jewish zombies who never really died when Solomon’s Temple was destroyed.

|

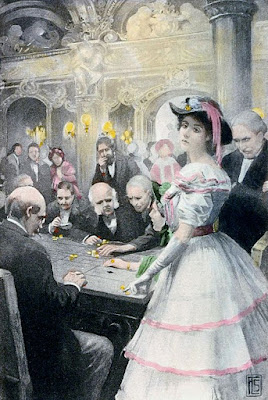

| Gwendolen at the roulette table |

Is it any wonder then, that Leavis suggests we cut away the

Jewish half and rename the remaining half Gwendolen

Harleth? Yet Gwendolen is a narcissist. During the course of the story, her

character undergoes a sea change thanks to her acquaintance with Deronda. This

(Jewish) reader, however, found Gwendolen to be an unsympathetic character, and

did not like reading about her at all. All I wanted to do was get to the Jewish

stuff.

In spite of these shortcomings, the two stories provide the reader with a deeper understanding of the two societies—English and Jewish—by contrasting their attitudes and behaviors. The patronizing bigotry of the English is palpable and there are many examples of this scattered throughout the book. After pawning her necklace to recover money lost at the gambling table, for example, “Gwendolen’s dominant regret was that after all she had only nine louis to add to the four in her purse: these Jew dealers were so unscrupulous in taking advantage of Christians unfortunate at play!”

Deronda’s Jewish heroine, Mirah Lapidoth, has been deeply

marked by treatment with such condescension, to the point that she seems

ashamed to admit or own her heritage. Mirah, in fact, appears to agree that Jews

are a malign presence in the world. She fears for Daniel to know of her Jewish

identity during their first meeting:

“You want to know if I am English?” she said at last, while Deronda was reddening nervously under a gaze which he felt more fully than he saw.

“I want to know nothing except what you like to tell me,” he said, still uneasy at the fear that her mind was wandering. “Perhaps it is not good for you to talk.”

“Yes, I will tell you. I am English-born. But I am a Jewess.”

Deronda was silent, inwardly wondering that he had not said this to himself before, though any one who had seen delicate-faced Spanish girls might simply have guessed her to be Spanish.

“Do you despise me for it?” she said presently in low tones, which had a sadness that pierced like a cry from a small dumb creature in fear.

“Why should I?” said Deronda. “I am not so foolish.”

“I know many Jews are bad.”

When Deronda meets Mirah, she is in bad straits. Looking for

a way to help her, Daniel brings the penniless, homeless Jewish girl to his friends

the (non-Jewish) Meyrick family, and on being introduced to them, Mirah’s first

words are, “I am a stranger. I am a Jewess. You might have thought I was

wicked.”

Daniel determines to help Mirah find her long lost mother

and brother, but the thought of spending time among Jews for this purpose,

makes him nervous. He knows his prejudices are just that, but finds them

difficult to ignore:

Deronda’s thinking went on in rapid images of what might be: he saw himself guided by some official account into a dingy street; he entered through a dim doorway, and saw a hawk-eyed woman, rough-headed, and unwashed, cheapening a hungry girl’s last bit of finery; or in some quarter only the more hideous for being smarter, he found himself under the breath of a young Jew talkative and familiar, willing to show his acquaintance with gentlemen’s tastes and not fastidious in any transactions with which they would favor him—and so on through the brief chapter of his experience in this kind.

There is a perception by Victorian society as portrayed in Deronda, of the Jews as unsavory. At the same time, when the English encounter an example of Jewish refinement, as embodied by our Jewish heroine Mirah, the response is to wish that the Jewish part of her would somehow disappear:

“She says herself she is a very bad Jewess, and does not half know her people’s religion,” said Amy, when Mirah was gone to bed. “Perhaps it would gradually melt away from her, and she would pass into Christianity like the rest of the world, if she got to love us very much, and never found her mother. It is so strange to be of the Jews’ religion now.”

Deronda attempts to find Mirah work as a singer for ladies’

gatherings, and as a result, we are party to some behind-the-scenes gossip.

Gwendolen several times refers to Mirah as the “little Jewess,” and Jews are characterized

by Lady Mallinger as “bigoted.” The very fact of Mirah’s Jewishness is

understood by her as an illogical bias and a rejection of accepted facts:

“She has very good manners. I’m sorry she is a bigoted Jewess; I should not like it for anything else, but it doesn’t matter in singing.”

The fact that Eliot would tackle such a sticky subject shows

that she was an original thinker. Raised in a strict Evangelical Anglican home,

Eliot read the bible every day, and was religiously fervent. Over time,

however, through her reading and various acquaintances, she became a skeptic,

while retaining a keen interest in the history of religion. It was while

working on her English translation of a German book on early Christianity,

published as The Life of Jesus Christ

Critically Examined (1846), that Eliot first became fascinated with Judaism

and the Jewish people. This was quite a change in outlook for someone who had

previously written of the Jews:

Extermination up to a certain point seems to be the law for the inferior races—for the rest, fusion both for physical and moral ends.

Eliot’s Daniel Deronda

was a clear attempt to educate the public, as she had educated herself

regarding the Jewish people and their religion. Eliot had grown up surrounded

by anti-Jewish prejudice. In 1830, when Eliot was ten years old, the House of

Commons debated a bill for the Removal of Jewish Disabilities (which failed to

pass). During the debate, historian Thomas Babington Macaulay remarked that it

is not just that the Jews had no legal rights to participation in normative English

society, but that “three hundred years ago they had no legal right to the teeth

in their heads.”

|

| George Eliot's grave in Highgate Cemetery |

Deronda was a

means of fighting back against the English view of the Jews as something repugnant

and uncivilized. Eliot, as England’s most celebrated writer, meant to humanize

and dignify the Jewish people before English society—to rid Victorian England

of its ingrained antisemitic prejudices—to show the English the worth and value

of what came before Christianity, informs it today, and continues to persist in

spite of the pervasiveness of Christian belief in the West.

The Jews of her time gave Eliot’s efforts a kind reception. Britain’s

chief rabbi at that time, Hermann Adler, expressed his “warm appreciation of

the fidelity with which some of the best traits of Jewish character have been

depicted.” When prominent London Jew Haim Guedalla sent Eliot a laudatory note,

the novelist responded, “No response to my writing is more desired by me than

such a feeling on the art of your great people, as that which you have

expressed to me,” a far cry from her former call for extinction of the entire

Jewish “race.”

David Kauffman, a professor at the Jewish Theological

Seminary in Budapest, wrote an article about Daniel Deronda, stressing Eliot’s philosemitism. Eliot responded by

writing to Kauffman as follows:

Excuse me that I write but imperfectly, and perhaps dimly, what I have felt in reading your article. It has affected me deeply, and though the prejudiced and ignorant obtuseness which has met my effort to contribute something to the ennobling of Judaism in the conception of the Christian community and in the consciousness of the Jewish community, has never for a moment made me repent my choice, but rather has been added proof to me that the effort was needed—yet I confess that I have a un-satisfied hunger for certain signs of sympathetic discernment, which you only have given.

Jews have always prayed for the return to Zion. Eliot was

well aware of this fact as she prepared to write Deronda. Eliot and her partner John Lewes visited the Judengasse

in Frankfurt, attended a Sabbath service in a synagogue in Mainz, and visited

both the Altneuschul and the ancient Jewish cemetery in Prague. The two

purchased books about Jewish law and theology, and Eliot published an essay

that stood as a plea for Jewish national and social rights, The Modern Hep!

Hep! Hep!

Eliot’s protozionistic concept of Zionism before Zionism ever

was, is well expressed in Deronda by

Mirah’s long lost brother Mordecai, also known as Ezra*:

“In the multitudes of the ignorant on three continents who observe our rites and make the confession of the divine Unity,† the soul of Judaism is not dead. Revive the organic centre: let the unity of Israel which has made the growth and form of its religion be an outward reality. Looking toward a land and a polity, our dispersed people in all the ends of the earth may share the dignity of a national life which has a voice among the peoples of the East and the West—which will plant the wisdom and the skill of our race so that it may be, as of old, a medium of transmission and understanding. Let that come to pass, and the living warmth will spread to the weak extremities of Israel, and superstition will vanish, not in the lawlessness of the renegade, but in the illumination of great facts which widen feeling, and make all knowledge alive as the young offspring of beloved memories.”

When the reader meets Mordecai, he is already ill with tuberculosis and hasn’t much time left.

He is desperate to impart his ideas to a Jew of the next generation who will carry

the flame. Daniel Deronda happens into the bookstore where he works, and

Mordecai becomes excited, sure he is the one.‡ When questioned however, Daniel

denies he is a Jew. Mordecai, disappointed, believes Deronda cannot then be his

disciple.

As time goes on, however, it becomes clear that Deronda must be the

right person for the job of carrying on Mordecai’s life’s work, and when Daniel

at last discovers his heritage, there is joy all around. At the same time, he

has the sad duty of explaining things to Gwendolen, who has fallen in love with

him and hoped to marry him. After breaking the news that he is Jewish and is

about to embark on a great journey, Gwendolen struggles for understanding:

“What are you going to do?” she asked, at last, very timidly. “Can I understand the ideas, or am I too ignorant?”

“I am going to the East to become better acquainted with the condition of my race in various countries there,” said Deronda, gently—anxious to be as explanatory as he could on what was the impersonal part of their separateness from each other. “The idea that I am possessed with is that of restoring a political existence to my people, making them a nation again, giving them a national centre, such as the English have, though they too are scattered over the face of the globe. That is a task which presents itself to me as a duty: I am resolved to begin it, however feebly. I am resolved to devote my life to it. At the least, I may awaken a movement in other minds, such as has been awakened in my own."

|

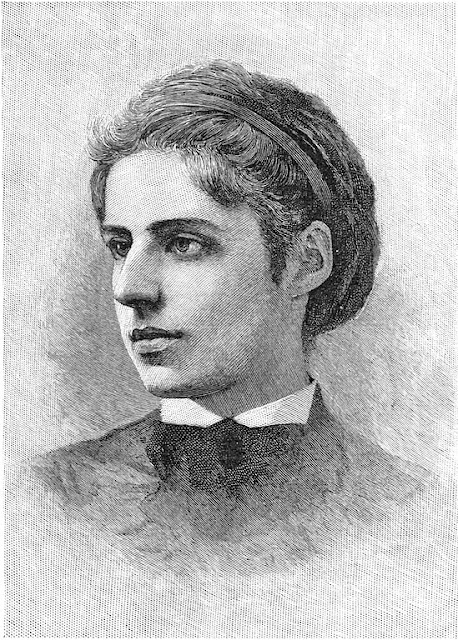

| Eliezer Ben-Yehuda at his desk, Jerusalem, c. 1912 |

Daniel Deronda may not have pleased Eliot’s non-Jewish readers and critics, and the Jewish characters may not have seemed quite human, but Eliot’s vision of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine was persuasive and inspiring for at least two Jews. Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the father of Modern Hebrew said Daniel Deronda was the reason he traveled to Palestine. In his memoirs, he wrote:

“After I read the novel, Daniel Deronda, in a Russian Translation, several times, I decided to leave the University of Dynaburg for Paris, where I would learn all that was necessary for my work in Eretz Yisrael.”

|

| Jewish American poet Emma Lazarus |

* This is confusing, as there is another Jewish

character of the same name.

† The Shema prayer

|

Or order from your favorite bookseller, using ISBN 9798985708424. Read all about it here! |

|