The Afterlife

Alexander Pechersky Led a Successful Prisoner Revolt at the Sobibor Death Camp. His Extraordinary Story is Also That of Millions of Soviet Jews.Attack on Rushdie mirrors 1925 killing of writer who satirized Vienna antisemitism

In November of 2018, at the National Arts Club in New York City, I attended a screening for the film Sobibor, which was described in the program as “First Russian Oscar Contender About Holocaust” (sic). The screening was part of a promotional campaign to secure a nomination in the best foreign film category, and was presented by the film’s producers, along with the Alexander Pechersky Foundation and the Russian American Foundation. Annexed to the auditorium where the screening was to happen was a small exhibition about Alexander “Sasha” Pechersky and the uprising he led at the Sobibor concentration camp, which was the subject of the film.

Konstantin Khabensky, the film’s star and director, had come to the screening from Russia. A panel of historians and experts was convened. The audience consisted of members of the local Jewish community and the Jewish press, not a few of them Russian-speaking. A group of elderly Russian Jewish war veterans, some in uniform, all decorated with their medals, were seated near the front of the room. Among them was a woman who wore a yellow star button on her blouse to identify her as a Holocaust survivor.

In opening remarks, a scholar of Soviet Holocaust cinema commended the producers for making a Russian film about the Holocaust, a suppressed subject for most of the Soviet period. In fact, any acknowledgment of the unique nature of the tragedy experienced by Soviet Jews in painting, sculpture, poetry, fiction, history, public monuments and other forms of remembrance was practically forbidden. In a nation that suffered so profoundly, with as many as 27 million citizens perishing during the war, the official position was that it was wrong to divide the victims. At sites of mass killings, if there was any commemoration at all, it memorialized “peaceful Soviet citizens” who had died at the hands of “the German occupiers.” Sobibor might therefore be regarded as the Russian equivalent to Schindler’s List.

Films are subjective things and it’s not my intention to engage in criticism of a film released two years ago. Also, the quality of the film is of negligible importance to the larger story of Alexander Pechersky’s life and legacy. But there were many people in the auditorium who were moved to tears by the film, gasped at acts of brutality or laughed at an incident of comeuppance against the Nazis, just like they were watching a regular movie. Unless they’d read the literature about Sobibor and Pechersky, none could have detected the places where the film departed from historical fact, though a partial list would include: Leon Feldhendler (spelled “Felhendler” in recently-discovered archival documents), one of the leaders of the camp underground, wasn’t killed during the revolt; Pechersky didn’t carry the corpse of a young woman named Luka out of the camp in his arms; a Nazi named Frenzel wasn’t shot by Pechersky; there was no crematorium smokestack in Sobibor; and Shlomo Szmajzner, a young Polish prisoner, didn’t, as the end titles assert, hunt down and kill Gustav Wagner, perhaps the camp’s most notoriously brutal SS officer, and 17 other Nazis in Brazil.

At the conclusion of the film, one audience member did inquire about historical accuracy, in response to which the gathered historians offered a general defense of the artist’s right to bend documentary truth for the sake of the emotional one. The Holocaust survivor, a small but pugnacious woman in the Russian Jewish mold, rose to praise the film, which she had now watched for the second time, though it caused her pain in every cell in her body. “Never again!” she proclaimed. One of the veterans took the floor and affirmed that the film showed what had happened in his generation and hoped it would serve as a lesson for the future. He proceeded to make some observations about Arab aggression and, after meeting with a mixed response, resumed his seat.

Nobody in the audience subjected the film to the kind of scrutiny it met in the more exacting corners of the Russian Internet. A widely circulated op-ed written by a commentator on Garry Kasparov’s website accused the filmmakers, and by extension the Russian state, of evading the truth about Sobibor and the heroes it pretended to celebrate: Where was the reference to the Soviet citizens who filled the ranks of the camp guards? What of the local population’s complicity with the Nazis? How about the Soviet Union’s merciless attitude toward its own POWs? And might they have spared a word about the tribulations Pechersky experienced after the war on account of both his captivity and his ethnicity?

Hadi Matar, the man charged with the attempted murder of the distinguished novelist Salman Rushdie, admitted that he had only “read like two pages” of “The Satanic Verses,” Rushdie’s 1988 novel that angered fundamentalist Muslims around the world. Iran’s former Supreme Leader, Ayatalloh Ruhollah Khomeini, who announced a fatwa calling on all Muslims to murder Rushdie in 1989, hadn’t read it at all.Gil Troy: The Jewish and intellectual origins of this famously non-Jewish Jew

“The Satanic Verses” wasn’t the first – and won’t be the last – novel to provoke the rage of a fanatic who has no grasp of literature’s nuances.

In 1922, an Austrian writer named Hugo Bettauer published a novel set in Vienna called “The City Without Jews.” It sold a quarter of a million copies and became known internationally, with an English translation issued in London and New York. A silent movie adaptation, which has recently been recovered and restored, appeared in the summer of 1924. The following spring, a young Nazi burst into Bettauer’s office and shot him multiple times. The author died of his wounds two weeks later.

A novel published in a polarized city

As in the US today, there was a major gap between rich and poor in early 20th-century Vienna.

The impressive architecture of the inner city sheltered immense wealth, while there was desperate poverty in the working-class districts beyond. The opulence of the banks and department stores, the culture of the theaters and opera house – especially in the predominantly Jewish district of Leopoldstadt – inevitably stirred deep resentment.

In the years immediately preceding World War I, populist mayor Karl Lueger saw his opportunity: He could win votes by blaming every problem on the Jews. Many a Jewish refugee would later say that the antisemitism in Vienna was worse than Berlin’s. An impoverished painter living in a public dormitory in a poor district to the north of Leopoldstadt was inspired to build a new ideology following Lueger’s blueprint. His name was Adolf Hitler.

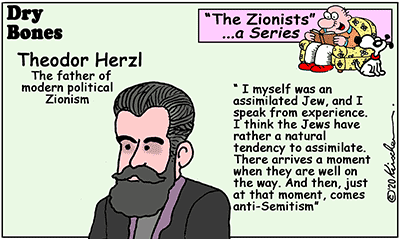

Editor’s note: Excerpted from the new three-volume set, “Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings,” the inaugural publication of The Library of the Jewish People edited by Gil Troy, to be published this August marking the 125th anniversary of the First Zionist Congress. This is the second article in a series. The first in the series is available here.

Theodor Herzl was born on May 2, 1860, in Pest, Hungary, across the River Danube from Buda. The second child and only son of a successful businessman, Jakob, he was raised to fit in to the elegant, sophisticated society his family and a fraction of his people had fought so hard to enter. But it is too easy to caricature his upbringing as fully emancipated and assimilated.

His paternal grandfather, Simon Loeb Herzl, came from Semlin, today’s Zemun, now incorporated into Belgrade. There, Simon befriended Rabbi Judah ben Solomon Chai Alkalai. This prominent Sephardic leader was an early Zionist, scarred by the crude anti-Semitism of the Damascus Blood Libel of 1840, inspired by the old-new Greek War of Independence in the 1820s—and energized by the spiritual and agricultural possibilities of returning the Jews to their natural habitat, their homeland in the Land of Israel. It is plausible that the grandfather conveyed some of those ideas, some of that excitement, to his grandson.

Still, the move from Semlin to Budapest, from poverty to wealth, from intense Jewish living in the ghetto to emancipated European ways in the city, placed the Herzl family at the intersection of many of his era’s defining currents.

The 1800s were years of change—and of isms. Creative ideas erupted amid the disruptions of industrialization, urbanization and capitalism. Three defining ideologies were rationalism, liberalism and nationalism—with each one shaping the next. The Age of Reason, the Enlightenment—science itself—rose thanks to rationalism. Life was no longer organized around believing in God and serving your king, but following logic, facts, objective truth. The logic of reason flowed naturally to liberalism, an expansive political ideology rooted in recognizing every individual’s inherent rights. Finally, as polities became less God-and-king-centered, nationalism filled in the God-sized hole in many people’s hearts. Individuals bonded based on their common heritage, language, ethnicity, or regional pride—and needs.

Ideas are not static. In an ideological age rippling with such dramatic changes, the different isms kept colliding and fusing, like atoms becoming molecular compounds. Some combinations proved more stable—and constructive—than others.

Liberalism combined with nationalism created Americanism, the democratic model wherein individual rights flourished in a collective context yielding the liberal-democratic nation-state. An offshoot of liberalism emphasizing equality more than rights fused with rationalism and created Marxism, although Karl Marx admitted his theories could only be enacted with irrational terror. Marxism with that violent streak, drained of liberalism, became communism, while a hyper-nationalism, rooted in blood-and-soil loyalty, and the kind of Marxist rationalism and totalitarianism also drained of any liberalism, created Nazism.

Amman, August 25 - A controversial, discriminatory proposal by a far-right Israeli lawmaker piqued interest in the wider region this week, and caused many to wonder why only disloyal Arabs living under Israeli rule would get deported to an area with one of the highest standards of living in the world, while the rest of the Middle East's population remains under oppressive control of corrupt dictatorships.

Amman, August 25 - A controversial, discriminatory proposal by a far-right Israeli lawmaker piqued interest in the wider region this week, and caused many to wonder why only disloyal Arabs living under Israeli rule would get deported to an area with one of the highest standards of living in the world, while the rest of the Middle East's population remains under oppressive control of corrupt dictatorships.