Meir Y. Soloveichik: ‘These Stones Are Not Silent’

Begin’s point is at once simple and profound, and what he wrote about the Western Wall is all the more true about the top of the Temple Mount itself, the site of “the great flame” and “the house that once stood” on that site. Are the stones silent or are they not? Is there still a profound Jewish connection to this site or not? If these stones are not silent, if they still whisper, “sending out their light across the generations,” how could a Jew possibly visit the sacred without being moved to prayer? And if the stones of the Temple Mount are indeed dead, silent, no longer linked to a living Judaism—if reverence for them is mere “old fashioned prejudice—then it makes sense to allow Jewish visitors as mere tourists, uttering nary a word, their silence paralleling those of the stones themselves. But then, why is the Western Wall itself a site of Jewish longing, and why should Jerusalem itself be of importance to Jews?Jerusalem isn't unified until the Temple Mount is ours - opinion

The question of what the Temple Mount embodies is bound up with the identity of the Jewish people, and of the State of Israel. Norman Podhoretz has suggested that the quest to divide Jerusalem is an attempt to assault the “scandal of Jewish particularity,” the notion that Jews have a unique destiny linked to one land on the earth. In the Bible, this “scandal” is made most manifest on the Temple Mount, where a universal God is described as choosing one mountain, among one people, as His eternal dwelling place.

It is just this that many seek to assault, denying the Jewish link to the land by seeking to ensure that the Mount remain devoid of Judaism if not of Jews. Begin similarly described the motivations of those who attempted to limit the sounding of the shofar and the singing of “Hatikvah” at the Wall: “Living testimony to a glorious past? A charter of rights hewn in ancient stone? Precisely for these reasons must the stones of the wall be taken from the Jews.” Thus a study of Jewish history reveals that the debate about Jewish rights in ancient Jerusalem, now as then, is linked to something larger: whether the Jewish reverence for this site, and the expressed longing for all that once occurred there, is mere “superstition,” or whether such faith is reified by the very stones that whisper still.

In the days before the May 6 Jewish pilgrimage, the newspapers of Israel, from the right-leaning Israel HaYom to the leftist Haaretz, published a poll revealing that at least 50 percent of Jewish Israelis believe that Jews should be allowed to pray on the Temple Mount. By the end of Independence Day, around 1,000 Jews had ascended to the Temple Mount, four times as many as those who had ascended on the last Independence Day before the pandemic. They were celebrated online by another minister of the government, Ayelet Shaked, heightening the contradictions in this coalition regarding a matter central to Israel’s identity. One fact is clear: The ancient stones are not silent, and the argument over the Temple Mount has only begun.

When we promise not to forget Jerusalem, what is it that we conjure up in our minds and hearts? What is it that we associationally capture in order to never forget Jerusalem?

While we might have idealized visions of what the place might have looked like, we also have extensive descriptions of how the heart of the city appeared. That heart, that crown, was the Temple, of course. It was resplendent, magnificent and beckoning, yet also aloof.

If, as we learn, the nations of the world flocked to Jerusalem, it was not to visit the existing rendition of the Mahaneh Yehuda shuk (outdoor market). It was to be awestruck and moved by the presence of God’s abode on Earth: The Temple.

The Temple was the epitome of the magnificence of Jerusalem and Jerusalem as a place was indistinguishable from the Temple that crowned it. Today, we have been blessed to once again be part of the life of the city that we have sworn eternal association with. We can marvel at its old walls and we can explore, with head-shaking wonder, the newly unearthed tunnels and passages that link us to Davidic times.

But, alas, that which made Jerusalem the great city is no more, and even worse, we are hard-pressed to even visit the site of its crown. Today, those who respectfully wish to visit the Temple Mount, the enormous Herodian creation on which the Temple was built, will undergo a process of humiliation and debasement for their loyalty.

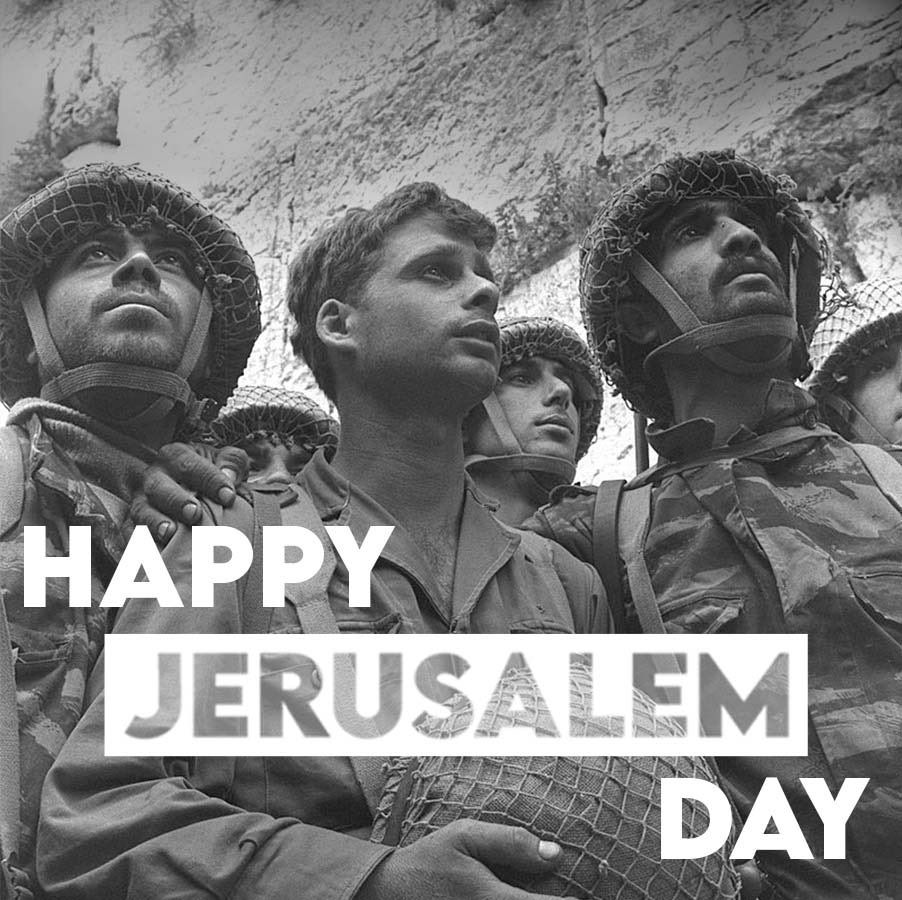

Ironically, while we triumphed miraculously some 55 years ago against an array of genocidal enemies and recaptured the Old City of Jerusalem, we almost immediately surrendered our greatest prize: the unfettered control of the Temple Mount. What ensued has been one of the greatest failures and embarrassments of the state of Israel: the willing severance of the connection of the Jewish people from its holiest site.