Bari Weiss: Stop Being Shocked

American liberalism is in danger from a new ideology—one with dangerous implications for JewsWas the French Enlightenment Anti-Semitic? Revisiting the Great Debate

The dominoes are falling hard and fast. That’s how you get pulpit rabbis who argue that Jews should not claim ourselves to be indigenous to the land of Israel. Or an organization meant to fight anti-Semitism that aligns itself with Al Sharpton. Or a tinderbox in the city with the largest Jewish population in the country, whose communal outfits seem to care more about lending cover to politicians than ensuring the physical safety of Jews.

Last month, I participated in a Zoom event attended by several major Jewish philanthropists. After briefly talking about my experience at The New York Times, I noted that if they wanted to understand what happened to me, they needed to appreciate the power of that new, still-nameless creed that has hijacked the paper and so many other institutions essential to American life. I’ve been thinking about what happened next ever since.

One of the funders on the call launched into me, explaining that Ibram X. Kendi’s work was vital, and portrayed me as retrograde and uncool for opposing the ideology du jour. Because this person is prominent and powerful enough to send signals that others in the Jewish world follow, the comments managed to both sideline me and stun almost everyone else into silence.

These people may be the most enraging: those with the financial security to oppose this ideology and demur, so desperate to be seen as hip; for their children to keep their spots at the right prep schools; so that they can be seated at the right tables at the right benefits; so that they are honored at Brown or Harvard; so that business does well enough that they can renovate their house in Aspen or East Hampton. Desperate to remain in good odor with the right people, they are willing to close their eyes to what is coming for the rest of us.

Young Jews who grasp the scope of this problem and want to fight it thus find themselves up against two fronts: their ideological enemies and their own communal leadership. But it is among this group—people with no social or political capital to hoard, some of them not even out of college—that I find our community’s seers. The dynamic reminds me of the one Theodor Herzl faced: The communal establishment of his time was deeply opposed to his Zionist project. It was the poorer, younger Jews—especially those from Russia—who first saw the necessity of Zionism’s lifesaving vision.

Funders and communal leaders who are falling over themselves to make alliances with fashionable activists and ideas enjoy a decadent indulgence that these young proud Jews cannot afford. They live far from the violence that affects Jews in places like Crown Heights and Borough Park. If things go south in one city, they can take refuge in a second home. It may be cost-free for the wealthy to flirt with an ideology that suggests abolishing the police or the nuclear family or capitalism. But for most Jews and most Americans, losing those ideas comes with a heavy price. (h/t jzaik)

Conclusion: Why the Jews are still being cast as getting in the way of universal redemptionHow we can create a new conflict-free Middle East

Hertzberg’s argument also suggests, as we have already noted, reasons why we should expect antisemitism to recur as a disease of the radical, or fundamentalist versions of political or religious movements, including ones consciously ‘anti-racist’ in their own estimation. Hertzberg makes the point that Montesquieu was less hostile to Jewish demands for emancipation than Voltaire because he represented ‘a tradition of enlightened thinking that ran counter to all this intellectual absolutism in the name of an appreciation of the Jew and Judaism as one of the many valid forms of culture and religion.’ Trevor-Roper, in his review, fully grants this difference between the two. ‘Now that there is a profound difference between the philosophy of Montesquieu and the philosophy of Voltaire no one would deny; and it is equally undeniable that Montesquieu was the more liberal of the two. Montesquieu was a relativist: he believed that societies were formed by a plurality of forces, and that they differed from one another, and differed legitimately, in accordance with the differences of those forces. His attitude to minorities was logically the result of his general philosophy . . . On the other hand Voltaire, a far less subtle or consistent thinker, believed in the linear progress of mankind toward a unitary truth of ‘philosophy’, and tended to judge men by their willingness to move in that direction. He had little of Montesquieu’s respect for the non-intellectual pressures of tradition, custom, or social force. It was for this reason that Gibbon, a disciple of Montesquieu, ended by repudiating Voltaire as in some respects ‘a bigot, an intolerant bigot.’[19]

The fundamentalist wing, not only of the Enlightenment but of any radically reforming movement, political or religious, left or right, tends to be defined by its determination both to simplify the goals of the movement and to treat them as ‘unitary truths of ‘philosophy’‘ to which, if the movement is to succeed, everyone without exception must be brought to accord an equally unitary and comprehensive submission. It is the fundamentalist wing of any such movement, therefore, that has the most to fear from the obstinate facts of human diversity, not only in the shape of what Trevor-Roper terms ‘the non-intellectual pressures of tradition, custom, or social force,’ but in that of competing intellectual systems. Hence it is that wing of any such movement that will always stand in most need of a story that will somehow make it plausible to regard all such pressures and constructs as the work of alien forces endlessly striving to corrupt a social order otherwise ready and waiting to respond positively and without serious dissent to the proffered opportunity of universal redemption. That, it seems to me, is ultimately what Hertzberg’s book has to teach us concerning the enduring tendency to antisemitic delusion on the part of the more radical elements, not only of the French Enlightenment, but of more recent versions both of progressive and anti-progressive thought.

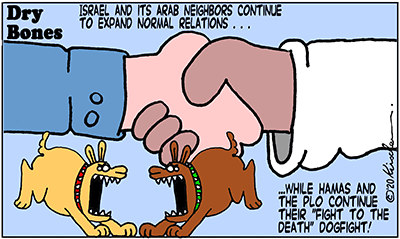

THE COMMON interests of the new allies will enable the creation of a new conflict-free Middle East.

Israel’s isolation is ending but its commitment toward its new allies has also become stronger. Israel today proves to the world that it has genuinely wanted peace; peace that will stabilize the region, create opportunities for Israeli youth, end its demonization by its neighbors, and allow it instead to be embraced. The opportunities that will be created will give the Palestinian youth political and economic stability, too, by enhancing cooperation between our countries on all levels.

In this process, we hope to also see a drastic change in the Palestinian leadership, and see leaders who can genuinely negotiate that which serves their people in an ethical manner.

Looking into the history of the Palestinian leaders, one cannot deny the lost opportunities to bring an end to the conflict with, Israel. February 2007, Palestinian leaders, representing Hamas and Fatah met King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, who wanted to resolve the differences between them.

After two days of negotiations, they presented Abdullah with a document that contained the agreements of all the assembled leaders. Everyone believed that this time the Palestinian leaders were serious. Abdullah asked them to honor their promise and had them swear on the Koran that the document was their final deal. Within 48 hours after their return, the Palestinian leaders broke their word.

Today, major players in the region will have a more crucial political role that will achieve peace and stability and enable the economies of all the countries involved to grow.

Today, a door has been opened to negotiations and alliances with new players in the region. The new players were always supportive of the Palestinian people and the UAE’s and Bahrain’s stance. Ethics and principles can never change.

Israel is officially a friend today, a friend we trust. And I truly believe that the moment those agreements were signed, all the parties involved had great intentions and will work closely together to make sure no one’s rights are violated and that the people of the region will eventually live in peace. A new dawn has finally begun.

.jpg)