Meir Y. Soloveichik: Sermons in Solitude: Jews of Faith Are Never Alone

On Thursday, March 13, my synagogue, Congregation Shearith Israel in New York City, announced it would not be holding services on Shabbat. To refrain from praying in a community is a traumatic moment for any house of worship. But for my community, the suspension of our communal Sabbath prayer due to the pandemic echoed down through history. Shearith Israel is the oldest Jewish congregation in America; tracing its origins to 23 souls that had landed in New Amsterdam, with a public synagogue first built in 1730, its members had joined one another in sanctifying the Sabbath for centuries. The last time Shearith Israel’s sanctuary had been abandoned by its congregants was 1776, when the patriot members of the congregation had fled in advance of the British taking Manhattan. But the very same Jews formed a minyan in Philadelphia, and the public rituals continued apace.Returning to Auschwitz on Holocaust Remembrance Day

Now, however, it was the minyan itself that had been rendered impossible.

I delivered a sermon on Friday afternoon—by conference call. What, I asked, does it mean to be joined, as a Jew, to others, precisely when we are forbidden from engaging with others? In my words to my community, I noted that on the Internet, many had been mentioning breakthroughs achieved by men of genius in solitude to suggest that forced aloneness might have unexpected advantages. After all, the argument went, Isaac Newton discovered the rules of calculus while in quarantine. But what interested me more, I said, was what I had learned about another insight achieved by Newton while in a period of solitude created by a plague: his conceptualization of gravity. A student described Newton’s eureka moment:

In the year he retired again from Cambridge on account of the plague to his mother in Lincolnshire & whilst he was musing in a garden it came into his thought that the same power of gravity (which made an apple fall from the tree to the ground) was not limited to a certain distance from the earth but must extend much farther than was usually thought – Why not as high as the Moon said he to himself & if so that must influence her motion & perhaps retain her in her orbit…

In his solitude, Newton conceived of a gravitational bond that could exert its power over long distances—that could even span heaven and earth. It is, I suggested, a spiritual form of just such a bond that we now must discover, one that binds us to others and indeed binds those in Heaven and those on Earth. The Hebrew term for synagogue is Beit Knesset, a house of gathering, and it is called so because, in the rabbinic tradition, the phrase Knesset Yisrael refers to the mysterious bonds that connect Jews to one another. A synagogue is not merely a physical gathering of individuals, but rather, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik explained, it reflects “an invisible Knesset Yisrael, which embraces not only contemporaries, but every Jew who has ever lived.”

The synagogue is meant to embody this bond, this connection to all Jews past and present. But there are other ways to experience it, and those other ways can have a singular power of their own. Anatoly Sharansky concludes his prison memoir by reflecting that at times, in the solitude of his cell, he felt more connected to his people than in the prosaic bustle of his newfound freedoms:

How to enjoy the vivid colors of freedom without losing the existential depth I felt in prison? How to absorb the many sounds of freedom without allowing them to jam the stirring call of the shofar that I heard so clearly in the punishment cell? And, most important, how, in all these thousands of meetings, handshakes, interviews, and speeches, to retain that unique feeling of the interconnection of human souls which I discovered in the Gulag?

Our challenge, I said, was to attempt a Newtonian insight, to find what Sharansky had felt: to ponder the meaning of relationships, and our bond as Jews with one another, until we were able to see each other in synagogue once again.

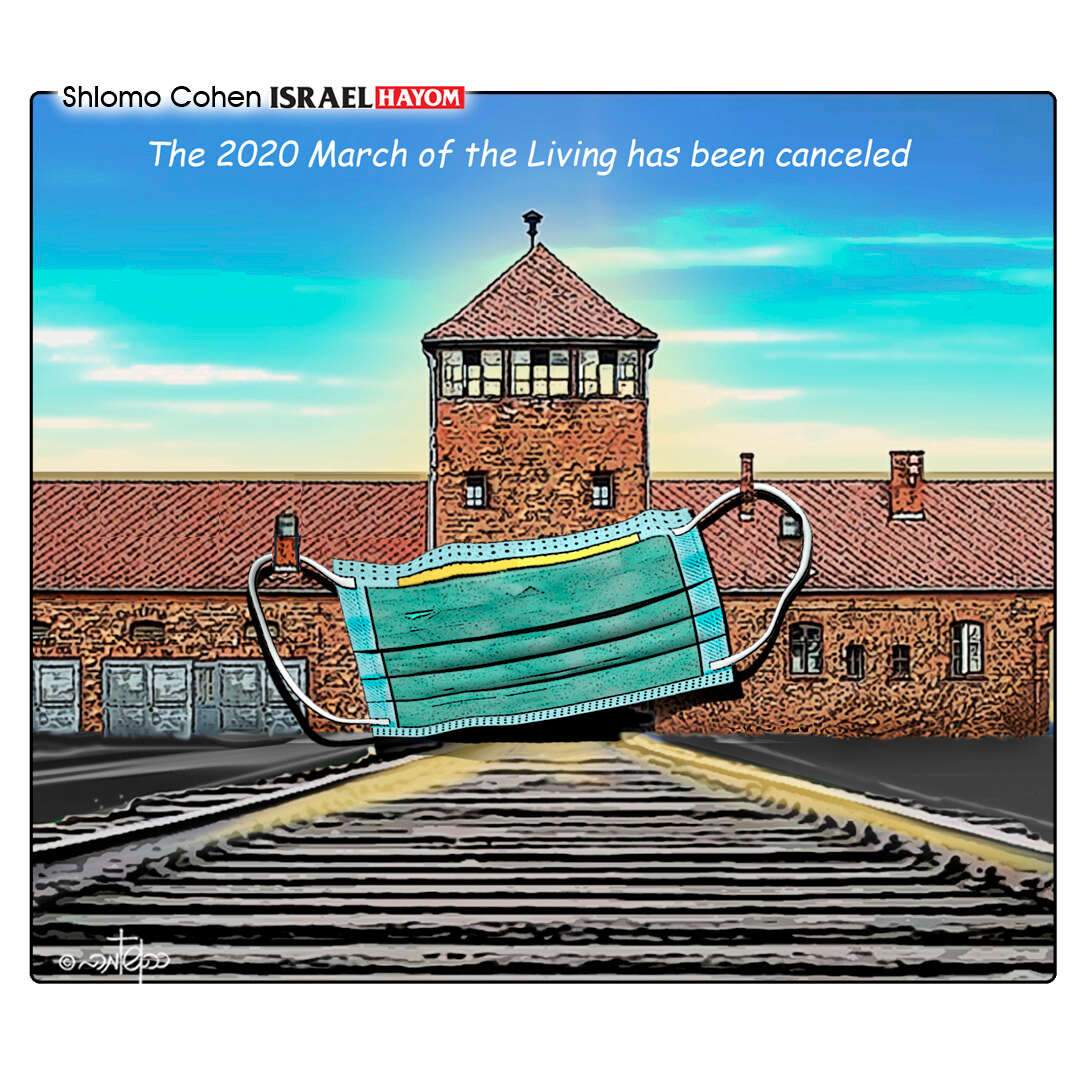

Unlike every other Holocaust Remembrance Day over these past few decades, on Monday and Tuesday the gate at the entrance to the Auschwitz extermination camp remained empty. The thousands who usually visit the camp every year have stayed at home due to the coronavirus epidemic - but we will be back, strong and with our heads held high.Ruthie Blum: Let us remember what the survivors are unable to forget

Auschwitz was here with us, in our generation, before the eyes of the entire world. Most of the world knew about Auschwitz as early as 1942, more so in 1943, and all the more in 1944, while trains filled with 50,000 Hungarian Jews to be exterminated were dispatched daily to the camp.

Some of the people who perpetrated these atrocities had even graduated from universities after studying enlightened German philosophers and

spiritual leaders such as Goethe, Heinrich Heine, and Immanuel Kant.

Auschwitz was a factory of death. It was there that the cursed Dr. Josef Mengele stood, and with a glance decided who was worthy of staying alive to bolster the camp's workforce, and who was to be sent to the gas chambers.

This year we could not walk the same route that those sentenced to death walked so many years ago, and no rendition of the Israeli national anthem HaTikvah will be heard in this valley of Jewish suffering. Even so, every one of us knows that the memory lives on of the Nazis, who threw millions of innocents into gas chambers and planned to eradicate an entire people from the face of the Earth.

But it is this people, our people, who are the people of eternity and will remain so until the end of time.

Holocaust survivors do not need annual ceremonies to remind them of the Nazi atrocities that they endured or of the family members that Adolf Hitler's henchmen slaughtered during World War II. No, those memories are just as inked in their hearts and minds as the numbers tattooed on their forearms.

Indeed, it is not those people who require the admonition "Never Forget," but rather the rest of the world. It is also a mantra for subsequent generations of Jews to repeat and forge a collective memory of events that we did not experience firsthand, but which require our ongoing attention. If, that is, we are to recognize and combat anti-Semitism in all its ideological – and military – manifestations.

The Knesset thus ruled in 1951 that Holocaust Remembrance Day would be marked on the 27th of the Hebrew month of Nissan, which falls between Passover and Israel Independence Day – two celebrations of freedom, victory, and a return to the Jewish homeland.

In Israel, then, Yom Hashoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day) is particularly significant. Not only was the Jewish state established in the wake of the Holocaust, but many survivors fought and were killed in the 1948 War of Independence.

Their stories of unparalleled heroism in spite of unfathomable victimhood are recounted each year at the main ceremony at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem on the eve of Yom Hashoah and at other locations during the following 24 hours. On the day itself, everyone in the country stops in his/her tracks at the sound of a siren to stand in silence for two minutes.

But not this year.

Thanks to coronavirus lockdowns – the emphasis of which ostensibly is to protect the elderly – the ceremonies are void of participants. With the exception of speeches by prominent politicians and performances by singers to empty halls, all commemorations and survivor testimonies have been held online and televised.

What makes this especially sad is the fact that the aging survivors – most of whom are not adept at Internet communication – have been living in isolation for weeks as it is. One survivor told Channel 12 on Monday evening that the hardest part about being alone is the lack of distraction from his daily traumatic memories. He explained that without people around, he finds it harder to push away the ghosts of his past.

.jpg)