|

Or order from your favorite bookseller, using ISBN 9798985708424. Read all about it here! |

|

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of Ziyon|

Or order from your favorite bookseller, using ISBN 9798985708424. Read all about it here! |

|

Varda Meyers Epstein (Judean Rose)

Varda Meyers Epstein (Judean Rose)Protocols: Exposing Modern Antisemitism posed an interesting problem for this once-a-week book reader. It is my habit to read books only on the Sabbath, when my computer is shut down for the duration. Since it is the Shabbat, when writing and drawing are forbidden, the use of a highlighter is similarly off-limits. How then, can one mark important passages for future reference, especially when there is something important on pretty much every page? That was the conundrum this writer encountered while reading the absorbing new read by Elder of Ziyon.

In general, the answer to my Sabbath "problem" of how to mark pages for future reference, is lots and lots of paper scraps, recycled

from old printouts. I cut the paper into strips before Shabbat, and slip the resulting scraps of paper between the

pages of the books I read. Then all I have to do is hope I can later figure out whether it was the

page on the left, or the page on the right that had the important passage, marked as it is, by only a flimsy paper placeholder. After Shabbat, I remove the paper scraps

one at a time and type out the page numbers on a document which I then save to my computer.

The problem with reading this particular book, written by Elder of Ziyon—by way of disclaimer, the host of this, my weekly column—is that I found myself slipping tiny pieces of paper between most of the pages. Everything I read seemed something worth remembering and revisiting. At a certain point, though armed with sufficient scraps of paper, I had to admit defeat: I could find nothing superfluous in Elder’s book.

There were things I didn’t know about before reading Protocols: Exposing Modern Antisemitism.

The writer has a clear and impressive command of his subject matter. As one

small example, I had never heard of the Jerusalem Declaration, an attempt

to modify the IHRA definition of antisemitism to exclude all criticism of

Israel. The writer informs, but often it is the way he frames his thoughts that

catches the reader’s attention:

“What other state, based on a national group, is ever told

to destroy itself?”

This is a new way of viewing an old and very tired story of

hatred.

New perspectives are always good, but Protocols also succeeds on the strength of the writing. In his prolific daily tweets, scoops, and blogs, Elder of Ziyon is distinguished by his economy of words. In his

book on modern antisemitism however, the

writer reveals his eloquence, as in this brief history of antisemitism:

Pharaoh saw Hebrews as a fifth column. Haman said the Jews didn’t respect the King’s laws. Antiochus said the Jews refused to assimilate. Christians said Jews killed their god. Jews stood accused of killing Gentiles, especially children. Jews charged interest on loans. Jews lived apart. Jews tried to assimilate and take over nations. Jews spread capitalism. Jews spread communism. Jews were a subhuman race.

One of the great things about Protocols is that it is an accessible read. It isn’t difficult to understand. That’s because Elder is good at

breaking things down for the reader. He uses plain talk for example, to

explain the various types of antisemitism (philosophical, social, racial, and

etc.) and how each type justifies its own brand of hate:

There are always “reasons” to hate Jews. The reasons are invariably garbage. But the excuses have a function, which is to have something on which to hang hatred of Jews and not feel like a bigot.

Protocols is based on sound and thorough research, making it a good resource and reference book for anyone. At the same time, Elder can explain difficult concepts in ways that are easy for any reader to understand. The average person may not know much about BDS. Elder presents BDS from a broader perspective, by providing information readers might otherwise never have heard or been exposed to:

BDS disregard for actual Palestinian welfare goes well beyond Israel and the territories. Palestinians in Lebanon who have lived there since the 1950s are barred, by law, from many jobs. They cannot buy land. They cannot build new housing even in overcrowded camps. Yet one would be hard-pressed to find a BDS advocate who demands that Lebanon offer basic human rights protection to their Palestinian residents. On the contrary, Lebanese bigotry against Palestinians is ignored and silenced, since the BDS narrative sees Israel as the only evil that may be discussed.

One of the best things about Protocols is that it is not

hampered by political correctness. The writer is unafraid to discuss, for example, black and

Hispanic antisemitism. Because the phenomenon exists, Elder gives us the

numbers, all properly sourced and footnoted:

Some 22% of blacks and 14% of Hispanic in America are antisemitic, according to a 2013 ADL poll. How exactly, can racism and antisemitism be tackled together when the victims of each consider the others to be the oppressors?

Reading a book like this, on such a difficult and often emotional topic, one is struck by the integrity of the writer. He does not shy away from the truth, and he is not going to lie. In fact it was Elder's integrity that motivated this writer to approach him in 2016 for a spot on his blog, a decision I have never regretted. One can feel clean writing from this small corner of the internet: the Elder of Ziyon blog. The book is a perfect echo of the blog in this respect. It's a clean read. You don't have to sift through bias to get to the facts.

Protocols offers

ample illustration that by definition, antisemites have kicked intellectual

honesty to the curb. This comes through loud and clear in the concluding paragraph of the chapter entitled “Judith

Butler’s fundamental dishonesty.”

No one is silencing anyone. All questions about Israel should be asked and forthrightly answered. But Butler doesn’t just ask questions—she attacks the very idea of Jews as people having the same rights as other people to self-determination. She disingenuously characterizes her criticisms as merely asking questions: she has no interest in the answers which an honest academic would welcome. She singles out Israel for vitriol way out of proportion to the supposed crimes to the point that it is the only state in the world assumed to be illegitimate. That isn’t debate, but hate—hate identical to that aimed at Jews throughout history, hate that also was justified as merely asking questions.

|

Or order from your favorite bookseller, using ISBN 9798985708424. Read all about it here! |

|

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of ZiyonBut our circumstances rarely fall into the category of "normal." Antisemitism has morphed into anti-Zionism. Just as we have historically been attacked for their Jewish identity -- now Jew-haters feel free to attack Jews for having any connection to Israel.

Einat Wilf, in The BDS Pound of Flesh, describes how the haters -- under the guise of anti-Israel activism -- bully Jews to relinquish the Zionism component of their Jewish identity before they will be accepted in progressive circles.

Her advice?

The only response to anti-Zionism, is Zionism.

How does that work?

A new book claims that Zionism is more than a conscious option open to Jews to

express their Jewish identity. Instead, Zionism is developing into a key,

indispensable element of Jewish identity. More than that: Zionism today is

becoming the glue that will maintain Jewish identity and strengthen it going

forward. The author, Gol Kalev, is a former Wall Street investment banker, now

living in Israel, where he writes for The Jerusalem Post and is the

chair of the America-Israel Friendship League Think Tank.

[Disclaimer: I helped proofread his book]

In his new book, Judaism 3.0: Judaism's Transformation To Zionism, Kalev writes:

Judaism 3.0 is a recognition that the organizing principle of Judaism has shifted from its religious element (Rabbinic Judaism) to its national element (Zionism). This shift is occurring without any compromise to the religious aspect of Judaism, and indeed only strengthens it. As this book shows, Zionism is increasingly becoming the relevant conduit through which Jews relate to their Judaism and the prism by which the outside world perceives the Jews. [p. 11]

He contrasts Judaism 3.0 with Judaism 1.0, when the original organizing principle was the Temple and the physical presence of the Jewish people in Judea -- and with Judaism 2.0, (or Rabbinic Judaism) after the Temple was destroyed and the Jews were exiled. The Temple was replaced by the synagogue and the sacrifices were replaced with prayer. This is when "the insular ghetto replaced the insular life in Judea, and the yearning to return to Zion replaced the actual presence in Jerusalem. [p. 12]"

While he applies this broadly, Kalev also devotes a portion of his book in explaining how this applies to American Jews, at a time when American Jews face a high rate of assimilation on the one hand and outright intimidation and attacks both on colleges and in the streets on the other.

In Chapter VI, The Transformation of Judaism -- American Jews, Kalev notes that political Zionism originally had little to offer Jews in America. Political Zionism was a way to address the misery of the Jews suffering from antisemitism. That was a powerful message in Europe, but America in the 20th century, by contrast, offered Jews freedom and a level of acceptance that they had not experienced in Europe. Jews integrated in American society. They did not need Zionism, and saw it as an encumbrance if not a threat to their status in America.

This integration led to a change in their Jewish identity in America. There was a denationalization from 'Judea' -- the yearning to return to 'Judea' and the association with Israel changed. Judaism went from a nation-religion to being reduced to being a mere religion.

And then on top of that came the secularization.

With the weakening of religion as the glue that anchored Jewish identity, over the past 80 years, other 'glues' served as substitutes to maintain that sense of Jewish identity:

1. Memory of the Holocaust: The Holocaust has been the most significant Jewish issue that united the Jews in the second half of the 20th century through today. The Holocaust, along with its lessons and memories, drives Jewish organizational policy and has dominated much of the Jewish community ethos...

2. Nostalgia for Ashkenazi/Eastern European roots: The second American Jewish glue was the culture of Yiddish, the shtetl, Jewish food (gefilte fish, bagel and lox) and Eastern European Jewish heritage. [p. 139]

According to Kalev, while the memory of the Holocaust -- and nostalgia for the Eastern Europe past -- have succeeded in replacing "the fading glues of religion, insularity and discrimination," memories of the Holocaust are fading as the generations of Holocaust survivors die. The same holds true for nostalgia for "the old country" -- which may actually be for the best.

On this point Kalev notes:

Astonishingly, nostalgia to the old country became nostalgia to values and elements of life which the Jews utterly detested while they were there. The ghetto life in Poland that was considered miserable in real time, became idolized in America...The retroactive glorification of Yiddish and Polish/Russian old country was done since there was no tangible connection to the real old country -- to Zion. [143; emphasis added]

Today, in the face of the weakening if not outright lack of "glues" for their Jewish identity, for a growing number of Jews, as important as their Jewish identity may be for them, it takes a back seat to other roles and other cultural identities. He is less likely to bring up his synagogue or Jewish school and more likely to bring up his college, a country club or his job. Instead of discussing the weekly parsha, he is more likely to want to talk about the newest restaurant or move.

The concern that Kalev is focusing on in his book is not the Orthodox Jews who connect with their Jewish identity through its religious component, nor what he refers to as "engaged Jews" who are active in Jewish causes and events.

Instead, the concern is for the majority of the Jews for whom being part of the Jewish community is not an important commitment and is low on their hierarchy of identities and priorities. The culture of the typical American Jew is the American culture. Jewish culture today for many is eating a bagel with lox and cream cheese.

What passes for Jewish culture today for the majority of Jews is not enough to maintain a sustainable connection to their Judaism.

One attempt to create a new expression of Jewish identity in progressive circles is found in the call for Tikkun Olam -- righting wrongs, doing good deeds, doing charitable work and making the world a better place to live. But Kalev writes that as an attempt to strengthen Jewish identity, it is doomed to fail, because

that is a very weak connector, since other groups engage in similar charitable actions.

If anything, it supports the notion of universalim -- of Judaism not being any different than any other group, religious or otherwise.

Moreover, a Jewish person engaging in such good-doing does not need to do it in a Jewish context. [p. 147]

In other words, the failure of Tikkun Olam as a bond to Judaism lies in the fact that it does the opposite of what it is alleged to do. Instead of connecting Jews to their unique identity, it promotes the idea of universalism, that Judaism is no different from any other religion. No different than any other group. This is especially true when Tikkun Olam is made all about human rights or humanitarian aid. The approach to inspiring Jewish identity through Tikkun Olam is self-defeating and doomed to failure.

Along with this weakening of Jewish identity in the US we are witnessing the ambivalence of Jews towards their Jewish leadership. In the 20th century, these leaders were not only looked up to by American Jews -- they were influential and other leaders, both national and international, met with them regularly.

But today, while the appearances continue, as new faces replace the old familiar ones, the Jewish community does not accept the Jewish leadership as unquestioningly as it once did. The new leaders do not carry the same gravitas, and besides -- American Jews are free to bypass them:

An American Jew can access his own tailor-made basket of leaders that suits his own evolving preferences: A rabbi, a teacher, a blogger, a progressive Jewish thinker, a comedian, a tour-guide he had in Israel or an Israeli political leader. Hence the Jew can now turn away from Jewish Federations, the UJA and other Jewish structures as the point of orientation for Jewish leadership, and instead turn towards Israel. [p. 151]

Going a step further, Kalev suggests the same applies to the end of the old Jewish icons. He contends that Jerry Seinfeld, Barbara Streisand and Jon Stewart are no more personifications of today's Judaism for those less affiliated than J. R. Ewing and his family are personifications of today's Dallas. Similarly, the old image of the Woody Allen stereotype of the "weak" Jew is now historic and no longer contemporary. Jewish symbols like Yiddish, a pastrami sandwich and bagels & lox are no longer singularly relevant to the Jewish identity as much as they have become "relevant to Americans of all backgrounds as a Jewish reference point...This is just like most customers in Italian restaurants are not Italian and most of those ordering Chinese takeout are not Chinese [p. 155]."

Enter the Israelization of the American-Jewish experience, where

thanks to the expanding array of relatable Israeli products and experiences, Judaism, through Zionism, is becoming increasingly relevant for the young American Jew. This is not by duty, but by choice. [p. 157; emphasis added]

Israel is no longer seen as an object of charity, as symbolized by the blue JNF box. That was in the past. Today, Israel is considered for what it offers, both internationally through its innovations, entrepreneurial spirit, art and culture, wine industry, academic centers and think tanks.

Kalev is not talking about inspiring a sense of Jewish pride and identity on the abstract level. He writes about concrete elements that American Jews can connect with as expressions of their Jewish identity. He suggests that this allows for a non-political connection with Israel, one that makes it possible to embrace Israel even while disagreeing with its policies -- something that Palestinian Arabs are beginning to realize:

The ability to disconnect or suppress politics paved the way for Palestinians in the West Bank to seek employment and mentorship by Israelis, and to even get funding for Palestinian start-ups from Israelis. This underscores how audiences can connect to Israel's success and desirability without endorsing or having a particular opinion on political issues. [p.158; emphasis added]

In a similar way, an American Jew who enjoys Israeli products does not do this as an endorsement of Israeli policies -- and will not suddenly stop identifying with Israel just because of a policy he disagrees with.

This does not ignore the fact that there are those who support BDS, but there too, due to the wide range of Israeli products it becomes evident that a literal boycott of all Israeli products is not the goal of the BDS movement, but rather the attention that can be gained by advocating for that cause.

The Israelization of the American Jewish community is therefore not a political phenomenon, but rather a cultural one. Israeli shows such as Fauda, Shtisel, Mossad 101 and Tehran are now showing up on American TV, with the result that American Jews are exposed to new Jewish icons.

Today, there is a lot of discussion about the current status of the connection between American Jews and Israel, a connection that is often portrayed as weakening. But there is a development in Zionism that may indicate a change that will help to strengthen those ties: Aliyah. Above, it was pointed out that there is a distinction between duty and choice. The same applies here, as Zionism is understood to go beyond immigration to Israel:

Zionism was perceived to be about the establishment of the State of Israel and making Aliya. Indeed, Aliya was essential in the early years of Israel, and for decades Israeli leaders urged American Jews to make Aliya. A Jew choosing to stay in the Diaspora was viewed with disappointment by Israelis, exerting some degree of guilt feeling -- someone who is not fulfilling his "duty" as a Jew. [161]

Not only were Jews expected to make Aliyah -- once they arrived they were expected to "Israelize". He was expected to shed his Diaspora identity and accept the Israeli culture. Today, there is still an expectation that upon making Aliyah, he will learn Hebrew and speak the language. In the 1920s, this expectation led to the formation of Hebrew Language Brigades which would reprimand people who did not speak Hebrew to each other. Kalev compares this to France today, which has tried to do something similar with its own immigrants. (An obvious difference is that unlike Muslim immigrants to France, Jews returning to Israel have a cultural and historical bond to the country.)

Today, the pitch is not to make Aliya but to maintain strong connections with Israel, including coming to visit Israel, but also to be exposed to the country without having to be on a path toward Aliya -- even experiencing Israel through a phone or laptop -- and don't forget Birthright trips. In addition to the practical side -- Aliyah -- there is also the ideological side. Kalev quotes Herzl that Zionism includes "not only the aspiration to the Promised Land...but also the aspiration to moral and spiritual completion."

The removal of the Aliyah requirement frees the way for unaffiliated American Jews to gain greater involvement and exposure to their Judaism through Zionism.

Today, since Judaism is not the defining element of the Jewish identity of most American Jews, in order for Judaism to be relevant, it has to be attractive and desirable. According to Kalev, the challenge is that "American Judaism needs to thrive in a non-committal environment."

An American Jew increasingly seeks the non-committal component for his various experiences, including for his affiliation with Judaism. But such non-committal affiliation is not possible under Judaism 2.0. The "ask" for the American Jew is to commit more: join and come to synagogue more often, send your children to Hebrew school, donate to the UJA, be a member of the Jewish community center and the other community Jewish organizations. [p.175]

Kalev contrasts this with those Israeli Jews for whom their religious affiliation is secondary to their Jewish identity. For such an Israeli Jew, his experiences in Israel shape his Jewish identity. Whatever his attitude toward Jewish religiosity may be, he remains committed and fully affiliated with Judaism. This is in contrast with what Kalev calls Judaism 2.0, where Jewish religious affiliation is the primary measure of the depth of one's connection to Judaism.

Those American Jews who are not among the 20% who are Orthodox or among the "strongly committed" are in danger and many are already disaffiliated. For them, Judaism 3.0 -- through Zionism -- is not necessarily going to bring them back to Judaism, but it does provide new ways to connect with Judaism. For some, this will prevent further estrangement, while for others it may serve as a catalyst to reconnect.

Today, one aspect of the lives of American Jews acting as a catalyst is antisemitism, which is reaching levels that just a few years ago would have been unimaginable. We are in a situation where Jews on campus are afraid to openly identify themselves as Jews.

But this rise in antisemitism can have a different effect as well:

This forces the unaffiliated and under-engaged Jew right back into his Jewish identity. But what is this identity? What is the point of Judaism that such a "Jew in abstention" passively seeks to "go back to?" It is not the synagogue which he has not frequented, nor the Holocaust that he does not think much about. The rise of such "Jewish existential thinking" leads the Jew into Israel as his identity benchmark -- this is the relevant association with his Jewish affiliation -- this is where he hears or thinks about Judaism.This reality is exactly what Herzl envisioned when he said that anti-Semitism is a propelling force into Zionism. [p. 177]

From this perspective, the current rise in antisemitism as anti-Zionism pressuring American Jews to criticize Israel actually has a positive dimension. Kalev argues that "the more an American Jew engages with the issues of Israel's policies, the stronger his connection to Judaism." Since much of the criticism directed towards Israel comes from "unaffiliated Jews" who are drifting away from Judaism anyway, "paradoxically, the 'coincidental' engagement with Israel of this group helps keep them Jewish." If Not Now could be seen as an example of this.

Kalev is not suggesting a plan of action. On the contrary, he sees this transformation where Zionism becomes a key component of Jewish identity as something natural and organic. And it is a process that is happening now. Judaism 3.0 is as natural a transformation as the transformation to Rabbinic Judaism from Judaism 1.0.

And the future of Jewish identity depends on it.

Varda Meyers Epstein (Judean Rose)

Varda Meyers Epstein (Judean Rose)George Eliot may not have been Jewish, but she understood

the Jewish hunger for the return to Zion. Mary Anne Evans, as she was

christened, cared about Jewish nationalism enough to make it the theme of her

final novel. Written a full 20 years before Theodore Herzl penned his utopian

novel Altneuland, and 40 years before

the Balfour Declaration, Daniel Deronda

ends with a Zionist bang: the eponymous hero is packed and ready to take off

for the East, where he is set on founding a homeland for his people in

Palestine.

Through most of the story, Daniel knows nothing of his Jewish

parentage. The ward of Sir Hugo Mallinger, an English gentleman, Deronda is

raised with every advantage and as such, feels uncomfortable to ask about his

origins. Mallinger has been so kind, and Deronda anyway assumes he is Sir

Hugo’s illegitimate offspring from an early fling—something that would be better

off left unsaid between them.

The 700-page book that is Daniel Deronda is not light reading and in actual fact is really

two stories. One story is a typical British romance, with a self-centered

British heroine, Gwendolen Harleth. The other is the story of a Jewish

awakening, in which a romance also takes place, in this case, featuring fictional

Jewish heroine, Mirah Lapidoth. The book is ponderous, even boring. The two

stories do not mesh well and only a dedicated reader would push through to the

end.

|

| Portrait of George Eliot by Samuel Laurence |

Many critics have written of the “Jewish half” and the “English half” of Daniel Deronda. F.R. Leavis split the novel into two in his The Great Tradition, and refers to the “good half” (the English half), and the “bad half,” (the Jewish half.) This is understandable, because the characters in the Gwendolen Harleth story are well-rounded and human, while the Jewish characters are wooden, and speak as if they stepped out of the Book of Isaiah. The reader imagines a kind of weird light in their eyes, as if they were immortal Jewish zombies who never really died when Solomon’s Temple was destroyed.

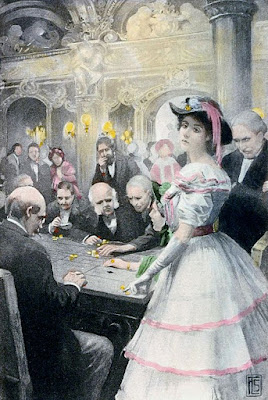

|

| Gwendolen at the roulette table |

Is it any wonder then, that Leavis suggests we cut away the

Jewish half and rename the remaining half Gwendolen

Harleth? Yet Gwendolen is a narcissist. During the course of the story, her

character undergoes a sea change thanks to her acquaintance with Deronda. This

(Jewish) reader, however, found Gwendolen to be an unsympathetic character, and

did not like reading about her at all. All I wanted to do was get to the Jewish

stuff.

In spite of these shortcomings, the two stories provide the reader with a deeper understanding of the two societies—English and Jewish—by contrasting their attitudes and behaviors. The patronizing bigotry of the English is palpable and there are many examples of this scattered throughout the book. After pawning her necklace to recover money lost at the gambling table, for example, “Gwendolen’s dominant regret was that after all she had only nine louis to add to the four in her purse: these Jew dealers were so unscrupulous in taking advantage of Christians unfortunate at play!”

Deronda’s Jewish heroine, Mirah Lapidoth, has been deeply

marked by treatment with such condescension, to the point that she seems

ashamed to admit or own her heritage. Mirah, in fact, appears to agree that Jews

are a malign presence in the world. She fears for Daniel to know of her Jewish

identity during their first meeting:

“You want to know if I am English?” she said at last, while Deronda was reddening nervously under a gaze which he felt more fully than he saw.

“I want to know nothing except what you like to tell me,” he said, still uneasy at the fear that her mind was wandering. “Perhaps it is not good for you to talk.”

“Yes, I will tell you. I am English-born. But I am a Jewess.”

Deronda was silent, inwardly wondering that he had not said this to himself before, though any one who had seen delicate-faced Spanish girls might simply have guessed her to be Spanish.

“Do you despise me for it?” she said presently in low tones, which had a sadness that pierced like a cry from a small dumb creature in fear.

“Why should I?” said Deronda. “I am not so foolish.”

“I know many Jews are bad.”

When Deronda meets Mirah, she is in bad straits. Looking for

a way to help her, Daniel brings the penniless, homeless Jewish girl to his friends

the (non-Jewish) Meyrick family, and on being introduced to them, Mirah’s first

words are, “I am a stranger. I am a Jewess. You might have thought I was

wicked.”

Daniel determines to help Mirah find her long lost mother

and brother, but the thought of spending time among Jews for this purpose,

makes him nervous. He knows his prejudices are just that, but finds them

difficult to ignore:

Deronda’s thinking went on in rapid images of what might be: he saw himself guided by some official account into a dingy street; he entered through a dim doorway, and saw a hawk-eyed woman, rough-headed, and unwashed, cheapening a hungry girl’s last bit of finery; or in some quarter only the more hideous for being smarter, he found himself under the breath of a young Jew talkative and familiar, willing to show his acquaintance with gentlemen’s tastes and not fastidious in any transactions with which they would favor him—and so on through the brief chapter of his experience in this kind.

“She says herself she is a very bad Jewess, and does not half know her people’s religion,” said Amy, when Mirah was gone to bed. “Perhaps it would gradually melt away from her, and she would pass into Christianity like the rest of the world, if she got to love us very much, and never found her mother. It is so strange to be of the Jews’ religion now.”

Deronda attempts to find Mirah work as a singer for ladies’

gatherings, and as a result, we are party to some behind-the-scenes gossip.

Gwendolen several times refers to Mirah as the “little Jewess,” and Jews are characterized

by Lady Mallinger as “bigoted.” The very fact of Mirah’s Jewishness is

understood by her as an illogical bias and a rejection of accepted facts:

“She has very good manners. I’m sorry she is a bigoted Jewess; I should not like it for anything else, but it doesn’t matter in singing.”

The fact that Eliot would tackle such a sticky subject shows

that she was an original thinker. Raised in a strict Evangelical Anglican home,

Eliot read the bible every day, and was religiously fervent. Over time,

however, through her reading and various acquaintances, she became a skeptic,

while retaining a keen interest in the history of religion. It was while

working on her English translation of a German book on early Christianity,

published as The Life of Jesus Christ

Critically Examined (1846), that Eliot first became fascinated with Judaism

and the Jewish people. This was quite a change in outlook for someone who had

previously written of the Jews:

Extermination up to a certain point seems to be the law for the inferior races—for the rest, fusion both for physical and moral ends.

Eliot’s Daniel Deronda

was a clear attempt to educate the public, as she had educated herself

regarding the Jewish people and their religion. Eliot had grown up surrounded

by anti-Jewish prejudice. In 1830, when Eliot was ten years old, the House of

Commons debated a bill for the Removal of Jewish Disabilities (which failed to

pass). During the debate, historian Thomas Babington Macaulay remarked that it

is not just that the Jews had no legal rights to participation in normative English

society, but that “three hundred years ago they had no legal right to the teeth

in their heads.”

|

| George Eliot's grave in Highgate Cemetery |

Deronda was a

means of fighting back against the English view of the Jews as something repugnant

and uncivilized. Eliot, as England’s most celebrated writer, meant to humanize

and dignify the Jewish people before English society—to rid Victorian England

of its ingrained antisemitic prejudices—to show the English the worth and value

of what came before Christianity, informs it today, and continues to persist in

spite of the pervasiveness of Christian belief in the West.

The Jews of her time gave Eliot’s efforts a kind reception. Britain’s

chief rabbi at that time, Hermann Adler, expressed his “warm appreciation of

the fidelity with which some of the best traits of Jewish character have been

depicted.” When prominent London Jew Haim Guedalla sent Eliot a laudatory note,

the novelist responded, “No response to my writing is more desired by me than

such a feeling on the art of your great people, as that which you have

expressed to me,” a far cry from her former call for extinction of the entire

Jewish “race.”

David Kauffman, a professor at the Jewish Theological

Seminary in Budapest, wrote an article about Daniel Deronda, stressing Eliot’s philosemitism. Eliot responded by

writing to Kauffman as follows:

Excuse me that I write but imperfectly, and perhaps dimly, what I have felt in reading your article. It has affected me deeply, and though the prejudiced and ignorant obtuseness which has met my effort to contribute something to the ennobling of Judaism in the conception of the Christian community and in the consciousness of the Jewish community, has never for a moment made me repent my choice, but rather has been added proof to me that the effort was needed—yet I confess that I have a un-satisfied hunger for certain signs of sympathetic discernment, which you only have given.

Jews have always prayed for the return to Zion. Eliot was

well aware of this fact as she prepared to write Deronda. Eliot and her partner John Lewes visited the Judengasse

in Frankfurt, attended a Sabbath service in a synagogue in Mainz, and visited

both the Altneuschul and the ancient Jewish cemetery in Prague. The two

purchased books about Jewish law and theology, and Eliot published an essay

that stood as a plea for Jewish national and social rights, The Modern Hep!

Hep! Hep!

Eliot’s protozionistic concept of Zionism before Zionism ever

was, is well expressed in Deronda by

Mirah’s long lost brother Mordecai, also known as Ezra*:

“In the multitudes of the ignorant on three continents who observe our rites and make the confession of the divine Unity,† the soul of Judaism is not dead. Revive the organic centre: let the unity of Israel which has made the growth and form of its religion be an outward reality. Looking toward a land and a polity, our dispersed people in all the ends of the earth may share the dignity of a national life which has a voice among the peoples of the East and the West—which will plant the wisdom and the skill of our race so that it may be, as of old, a medium of transmission and understanding. Let that come to pass, and the living warmth will spread to the weak extremities of Israel, and superstition will vanish, not in the lawlessness of the renegade, but in the illumination of great facts which widen feeling, and make all knowledge alive as the young offspring of beloved memories.”

When the reader meets Mordecai, he is already ill with tuberculosis and hasn’t much time left.

He is desperate to impart his ideas to a Jew of the next generation who will carry

the flame. Daniel Deronda happens into the bookstore where he works, and

Mordecai becomes excited, sure he is the one.‡ When questioned however, Daniel

denies he is a Jew. Mordecai, disappointed, believes Deronda cannot then be his

disciple.

As time goes on, however, it becomes clear that Deronda must be the

right person for the job of carrying on Mordecai’s life’s work, and when Daniel

at last discovers his heritage, there is joy all around. At the same time, he

has the sad duty of explaining things to Gwendolen, who has fallen in love with

him and hoped to marry him. After breaking the news that he is Jewish and is

about to embark on a great journey, Gwendolen struggles for understanding:

“What are you going to do?” she asked, at last, very timidly. “Can I understand the ideas, or am I too ignorant?”

“I am going to the East to become better acquainted with the condition of my race in various countries there,” said Deronda, gently—anxious to be as explanatory as he could on what was the impersonal part of their separateness from each other. “The idea that I am possessed with is that of restoring a political existence to my people, making them a nation again, giving them a national centre, such as the English have, though they too are scattered over the face of the globe. That is a task which presents itself to me as a duty: I am resolved to begin it, however feebly. I am resolved to devote my life to it. At the least, I may awaken a movement in other minds, such as has been awakened in my own."

|

| Eliezer Ben-Yehuda at his desk, Jerusalem, c. 1912 |

Daniel Deronda may not have pleased Eliot’s non-Jewish readers and critics, and the Jewish characters may not have seemed quite human, but Eliot’s vision of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine was persuasive and inspiring for at least two Jews. Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the father of Modern Hebrew said Daniel Deronda was the reason he traveled to Palestine. In his memoirs, he wrote:

“After I read the novel, Daniel Deronda, in a Russian Translation, several times, I decided to leave the University of Dynaburg for Paris, where I would learn all that was necessary for my work in Eretz Yisrael.”

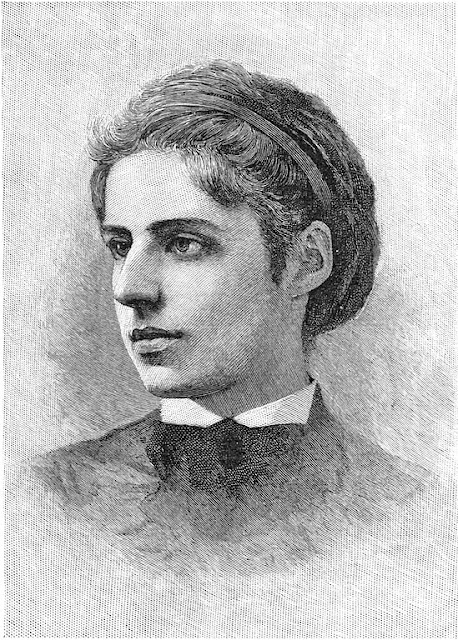

|

| Jewish American poet Emma Lazarus |

* This is confusing, as there is another Jewish

character of the same name.

† The Shema prayer

|

Or order from your favorite bookseller, using ISBN 9798985708424. Read all about it here! |

|

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of ZiyonThe line most often quoted from Frank’s diary—“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”—is often called “inspiring,” by which we mean that it flatters us. It makes us feel forgiven for those lapses of our civilization that allow for piles of murdered girls—and if those words came from a murdered girl, well, then, we must be absolved, because they must be true. That gift of grace and absolution from a murdered Jew (exactly the gift, it is worth noting, at the heart of Christianity) is what millions of people are so eager to find in Frank’s hiding place, in her writings, in her “legacy.” It is far more gratifying to believe that an innocent dead girl has offered us grace than to recognize the obvious: Frank wrote about people being “truly good at heart” three weeks before she met people who weren’t.

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of ZiyonBy RealJerusalemStreets

I hesitated. At first, I said to myself--no way.

The fiction I really like to read would be a good murder mystery. However, a novel based in 1943-1944 - and in Auschwitz?

Unsettling as the concept was, the author and publisher, Tom Hogan, and his bio piqued my curiosity.

Hogan grew up in a German village with his US military family after World War II. As an eight-year-old, he visited Dachau with his family. He wondered how many of his neighbors knew about and participated in the Holocaust.

Hogan taught at Santa Clara University after graduating from Harvard with an MA in Biblical Archeology and developed curricula in Holocaust Studies for college and high school.

Along with survivors' testimonies, he presented the Shoah to US audiences.

Hogan left teaching in the 1980s, to join a growing company as its first creative director. Perhaps you may have heard of Oracle? Next, his venture capital company launched over 50 startups and he co-authored The Ultimate Startup Guide.

After leaving the tech world, Hogan returned to teaching Holocaust and Genocide Studies at UC Santa Cruz before he retired and began to write fiction.

Hogan's Heroes was the name of the American sitcom popular from 1965-1971, where during World War II, the inmates of the prisoner-of-war camp, the fictional Stalag 13, did their best to sabotage the German effort. Their escapades led to humorous results involving Col. Klink and Sargent Shultz, and these Nazis were portrayed as bumbling comedic characters. Cast member Robert Clary had a number tattooed on his arm, as the Jewish actor had really spent 3 years in a concentration camp before arriving in Hollywood. He was often referred to as "cockroach" by the Nazis on the show, but it was a light feel-good program that always ended with Col Hogan's guys outsmarting the Germans.

Tom Hogan's The Devil's Breath is not light and not humorous. However, when the extermination camp details he has included get too heavy, readers are given a break to recover with his excellent character development. Lead characters Perla and Shimon Divko are transferred from the Warsaw Ghetto to Auschwitz and forced by Kommandant Rudolf Hess to solve a murder and a theft.

Hess is the only non-fiction character. In this genre, as opposed to memoirs, Holocaust expert Hogan is able to weave in historical information. I was at Auschwitz on a March of the Living trip years ago. Some of the facts are not only stranger than fiction, but worse as well, and I confess to skimming quickly over details of Kanada, the selection and gas chambers.

One example of adding positive information was the introduction of a drug connection along with the theft and murder of a Nazi officer in his office. Previously I was not familiar with Pervitin , but went on to read about how it was used by the Nazis later in the war. The details in the book fit the information I found.

While The Devil's Breath is not a light read and should have trigger warnings for today's crowds, I felt it important and well done enough to share. As there are fewer survivors to tell their stories, Hogan has found a new approach to educate the public about the horrors of the Holocaust.

Title: The Devil's Breath ISBN: 978-1-7369436-1-8

Tom Hogan 274 pages Paperback/Kindle

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of Ziyon Elder of Ziyon

Elder of ZiyonBuy EoZ's book, PROTOCOLS: EXPOSING MODERN ANTISEMITISM

If you want real peace, don't insist on a divided Jerusalem, @USAmbIsrael

The Apartheid charge, the Abraham Accords and the "right side of history"

With Palestinians, there is no need to exaggerate: they really support murdering random Jews

Great news for Yom HaShoah! There are no antisemites!