A Hasidic singer, a dozen boys and teens, a father of 11: All 45 Meron victims

The identification of all 45 victims from the Mount Meron tragedy has been completed, Israel’s Abu Kabir Forensic Institute said Sunday morning.

The victims, all male, included brothers, children as young as 9, young fathers, and rabbis. At least two families lost multiple children.

Among the victims of the fatal crush caused by overcrowding in a narrow walkway were 10 foreign citizens: six Americans, a British national, two Canadians, and an Argentinian.

The incident, which happened early Friday during celebrations of the Lag B’Omer festival, is the country’s deadliest-ever civilian disaster.

Police on Sunday said a man who took part in the pilgrimage was still missing and asked the public for help in locating him: Icht Haim Yitzhak, 39, was last seen at 8:30 p.m. on Thursday at Mount Meron. He is 6 foot 1 (185 centimeters), thin and bearded.

Dozens were buried Friday, but funeral services ceased during the Sabbath, from Friday evening until Saturday nightfall.

The Abu Kabir Forensic Institute said in a statement Sunday morning that by midnight it had completed the grim task of identifying all 45 victims.

By the morning 44 of the bodies had been released for burial and the last, at the request of the family, was to be released later in the day, the statement said.

High Court of Justice Torpedoed Government’s Attempt to Renovate, Secure Mt. Meron Site

In response to the State Comptroller’s warning in 2007, the state appointed a committee of five members to investigate the situation and make recommendations. By the end of 2011, the Israeli government decided to embrace the committee’s recommendation and nationalize the site, removing ownership from the trusts and transferring it to the state. This was met with a fierce struggle that was waged by some in the Haredi community, who feared losing control on the character of the site, and of their sources of income through the charity collections.Calls Grow for State Commission of Inquiry into Mount Meron Tragedy

At the end of 2013, the new Minister of Finance Yair Lapid, who served in a Netanyahu coalition government without the Haredi parties, signed an order expropriating the ownership of the place from the trusts, and transferring it to a new governmental company. But in January 2016, the government decided to dismantle the new company and transfer its responsibilities to the Holy Places Administration.

The Haredi associations petitioned the High Court of Justice, which issued an interim ruling that sent the parties to negotiations in order to reach an experimental model, instead of letting the government carry out the expropriation.

An attorney representing the Haredi trusts told Calcalist at the time that the High Court considered nationalizing the site an extreme measure, which should only be used after all the other measures had been exhausted.

Let’s hope that the High Court would consider the death of 45 Jews to mean that those less extreme options have been sufficiently exhausted and that no additional Jews need to lose their lives before the government is allowed to make the site less lethal.

The proposals that have been bandied about in the Israeli media on Sunday involve D9 bulldozers that would raze all the many decrepit structures surrounding Rashbi’s tomb, to create a plaza reminiscent of the wide-open area in front of the Kotel, where hundreds of thousands have been able to crowd together (in the years without a pandemic) without being crushed.

The History of Israel's Mount Meron

110 years ago, 100 people fell from a balcony at Mt. Meron; 11 were killed

The deadly crush in which 45 ultra-Orthodox pilgrims were crushed to death at Mount Meron on Thursday night was not the first safety-related disaster to occur there during Lag B’Omer celebrations. Exactly 110 years ago, 11 people were killed, and more than 40 were wounded, when a balcony railing collapsed at the holy site.1921 Jaffa riots 100 years on: Mandatory Palestine’s 1st ‘mass casualty’ event

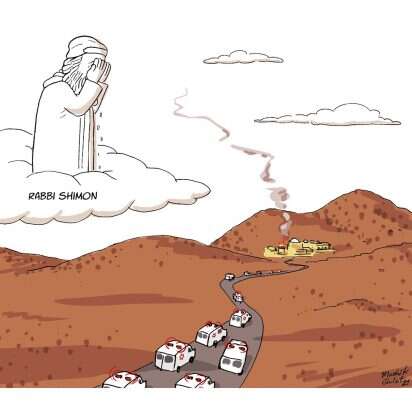

On May 15, 1911, Lag B’Omer night, at the gravesite of the second-century sage Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, at least 100 people fell some seven meters from a balcony after the railing surrounding it collapsed.

Bar Yochai is reputed to have died on Lag B’Omer. The date, poignant in the era of COVID-19, also commemorates the end of another plague some 2,000 years ago, which saw the deaths of 24,000 followers of Rabbi Akiva.

Back in 1911, almost four decades before the establishment of the State of Israel, there were no emergency medical forces present. The event was being secured by the Ottoman Safed police unit, the Walla news site noted in a report Saturday on past disasters and alerts at the northern Galilee site, which has become the second most-visited holy place in Israel after the Western Wall.

The railing on the balcony, along with part of the roof in an area where a large number of worshippers were present, broke apart, sending dozens plunging downward. Nine died in the immediate aftermath, and two more died the next day in the Rothschild Hospital in Safed, now known as the Bnai Zion Medical Center.

Fears of further disaster at the annual celebrations were frequently raised over subsequent decades, along with numerous reports that underlined the sense of relief when tragedy didn’t strike.

Israel last month marked its 73rd Independence Day, observed as always directly after its Memorial Day for fallen soldiers and victims of terrorism. The latter event carried a bittersweet distinction: For Israelis, the preceding year was by far the least bloody in their history — only three died in violent attacks — and the year before was second-calmest — with 11.

That these figures should be cause for celebration is an illustration of Israelis’ resignation to living in an environment with no parallel in the developed world — a reality that one of their preeminent novelists and peace activists calls, bleakly, death as a way of life.

For there is no education like experience, and in its nearly three quarters of a century of existence, this country has known three wars with multiple neighbors, two more in Lebanon, three in Gaza, two intifadas and innumerable individual hostile acts. But to make sense of the conflict today it is instructive to look further back still to the events of exactly a century ago, before there was a Jewish state or even a Palestine Mandate.

On May 1, 1921, in the interlude between Britain’s conquest of the land and the League of Nations’ ratification of its mandate, riots shook Palestine. It was the first time since the Crusades that civilians in the Holy Land had experienced what would later be termed, with grim sterility, a mass-fatality incident. And it was, for the Zionist movement, a turning point in its perception of the “Arab question” and its own relation to armed force and retribution.

The Balfour Declaration, the British conquest of the Land and the end of the Great War had produced euphoria in the Yishuv movement — that is, the Jews living in pre-state Israel — convincing it that dreams of sovereignty in Palestine were on the brink of fulfillment. But, as Israeli historian Benny Morris writes, the “massive violence of 1921 left an ineradicable impression on the Zionists, driving home the precariousness of their enterprise.”

The necessity of a strong defense — a conviction previously limited to a few diehards — now began trickling into mainstream Zionist thought.

Hi @TwitterSafety @Twitter: Why are you allowing this hashtag #الجسر_المقدس on your platform? These sinister tweets directly violate your “hateful conduct policy” by expressing astonishing hatred in the wake of human tragedy on Mount Meron. Remove this hashtag! #EndJewHatred pic.twitter.com/k7ojlLTpTx

— Arsen Ostrovsky (@Ostrov_A) May 2, 2021

Washington, April 29 - Congressional opponents of the Jewish State clarified today that they do not seek to eliminate American funding to advance that country's defense capabilities, but merely to tweak the provisions of that defense package to the minimal degree necessary for the funding to instead reach the violent criminals who want to cleanse Jews from the region between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea.

Washington, April 29 - Congressional opponents of the Jewish State clarified today that they do not seek to eliminate American funding to advance that country's defense capabilities, but merely to tweak the provisions of that defense package to the minimal degree necessary for the funding to instead reach the violent criminals who want to cleanse Jews from the region between the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea.