Weekly column by Vic Rosenthal

On Tuesday, Israel’s 24th Knesset was sworn in. They were asked to commit to “…be faithful to the State of Israel and to fulfill with devotion [their] cause in the Knesset.” The majority of them responded “I commit,” but four Arabs and one Jewish communist did not. The Arabs, members of the Hadash (communist) and Balad (“land" parties) said that they would commit to struggle against “occupation and apartheid” or “racism and racists.” The declarations were not accepted and the five were escorted out of the chamber. They will forfeit some privileges of Knesset membership until they make the proper declaration, as specified in the Basic Law for the Knesset. I have not been able to determine if they will also not get paid, although I’m not holding my breath.

This is not anything new. Arab MKs in 2013 left the ceremony before the singing of Israel’s national anthem, Hatikva. Then-MK Hanin Zoabi of the Balad party explained that “as an Arab woman born in this country, the anthem oppresses me and humiliates me.” The song expresses the “Jewish spirit yearning … to be a free people in our land, the land of Zion and Jerusalem.” Zoabi and other Palestinian nationalists reject the idea of a Jewish state; their official platform calls for a Palestinian state in Judea/Samaria and the “return” of the descendants of the Arab refugees of 1948 to the area of pre-1967 Israel and the establishment of a binational state. They consider themselves the “true owners of the soil,” and so the sentiments expressed in Hatikva are offensive to them.

All the Arab parties and the Arab-Jewish communist party are explicitly anti-Zionist. Balad is funded by Qatar; Mansour Abbas’ Ra’am party – which ironically (and in my opinion, outrageously) may end up supporting a Netanyahu coalition with its votes – is associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, the parent and patron of Hamas. The Basic Law for the Knesset says that “negation of the existence of the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state” disqualifies a candidate from standing for election to the Knesset. If it were enforced, probably none of today’s Arab MKs would qualify.

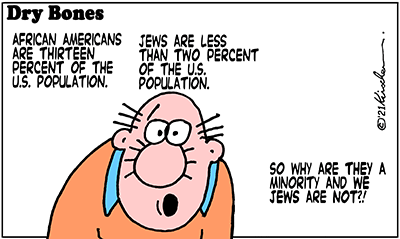

About 20% of Israel’s citizens are Arabs, mostly the descendants of Arabs that did not flee the area that became Israel in 1948. Some are residents of eastern Jerusalem who accepted Israeli citizenship when it was offered after the 1967 war (although most refused and remain permanent residents who can vote in municipal elections but not national ones). Arabs are an essential part of Israel’s economy and cultural life.

And they are not going anywhere. Meir Kahane argued that if they were not removed from the country, they would overtake the Jewish majority demographically; but as time has passed and the Jewish and Arab birthrates have tended to converge, this worry has receded. On the other hand, if it turns out that the political positions of the Arab MKs are representative of the population, then the presence of a large minority that opposes the existence of the Jewish state as such is exceedingly dangerous. Is there in fact such a minority?

It’s not a simple question. Several surveys in recent years show a large majority of Arab citizens of Israel are happy with their lives here, and would not choose to live in another country – certainly not in the Palestinian Authority or Gaza. Surprisingly, a recent poll shows that one-third of them even approve of the performance of PM Netanyahu, whom the Jewish Left constantly accuses of anti-Arab racism.

On the other hand, a large majority assert that they oppose the definition of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people as expressed in the Nation-State Law, and would prefer a state of all its citizens. But it seems – and anecdotal evidence supports the idea – that the economic and physical security that they find in Israel overrides ideological considerations.

This situation is not ideal, but is probably the best that can be expected. The ideological disagreement comes from the traditional Palestinian narrative, in which they see themselves as the aboriginal inhabitants of the land who were pushed aside and had their land violently stolen from them by a wave of European Jewish invaders. This story imparts a serious blow to the honor of the Arab community, honor that some of them believe can only be recaptured by the violent expulsion of the invaders. This is sometimes understood as a loss of honor to the Muslim ummah as well, in which case there is a strong religious imperative to regain it. The combination of these beliefs can inflame their holders to commit acts of violence, even suicide terrorism.

While most Arabs in Israel are not extremists, the narrative powerfully influences their collective consciousness. Sometimes this is expressed in ways that shock us, as in the recent welcome given to a terrorist who was released after 35 years in prison for the gruesome torture and murder of a young Jewish soldier.

The Palestinian narrative is taught in the Israeli-Arab school system, and by left-wing Jewish and Arab teachers in universities. It pervades Arab culture: theater, poetry, and music reflect it. Although hatred for Jews and the glorification of martyrdom in the service of the cause is not part of official curricula as it is in Gaza or the Palestinian Authority, it is part of the conventional wisdom in Arab communities that anti-Israel terrorists are heroes and heroines even if their actions are thought impractical. And the Palestinian narrative is an essential part of the ideology of Arab intellectuals, including members of the Knesset, whether or not it is connected to a religious, Palestinian nationalist, or pan-Arab message.

Could there be an Arab consciousness that is truly accepting of the fact of a Jewish state, a consciousness that understands that there is nothing fundamentally illegitimate about the state, and one that can see the decision to live as a minority in a state that belongs to someone else as not shameful?

That would require teaching a new understanding of the history of the state that sharply contradicts the existing Palestinian narrative. It would need to take into account the actual history of the Jewish people and the Palestinian Arabs in the region, rather than the myths that have been created for political purposes. It would have to describe the migrations of the various groups that make up today’s Palestinians, and not make up stories about Philistines and Canaanites. It would need to accept that Jews lived in the region for thousands of years, and built a Temple in Jerusalem (and incidentally that Jesus was a Judean). Finally, it would need to drop the ideas that Palestinians are victims of Jewish colonialism, and that they are indigenous and we are not.

Unfortunately, the academics that would teach this version of the story, a version that could be accepted by both Jews and Arabs because it is true, are rare indeed. The post-modern view that all narratives are equally true (or false) is common today. The politicians that would adopt it would be forced to give up political advantage gained by stirring up resentment and hatred, placing them at a disadvantage to those who didn’t (which is why all Arab MKs at least pay lip service to Palestinian nationalism).

I don’t expect this to happen, at least not today with today’s cast of characters, both Jewish and Arab. So the best we can hope for is an increased pragmatism, an understanding that everyday life is more important than ideology. It’s not perfect, but we can live with it.

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of Ziyon