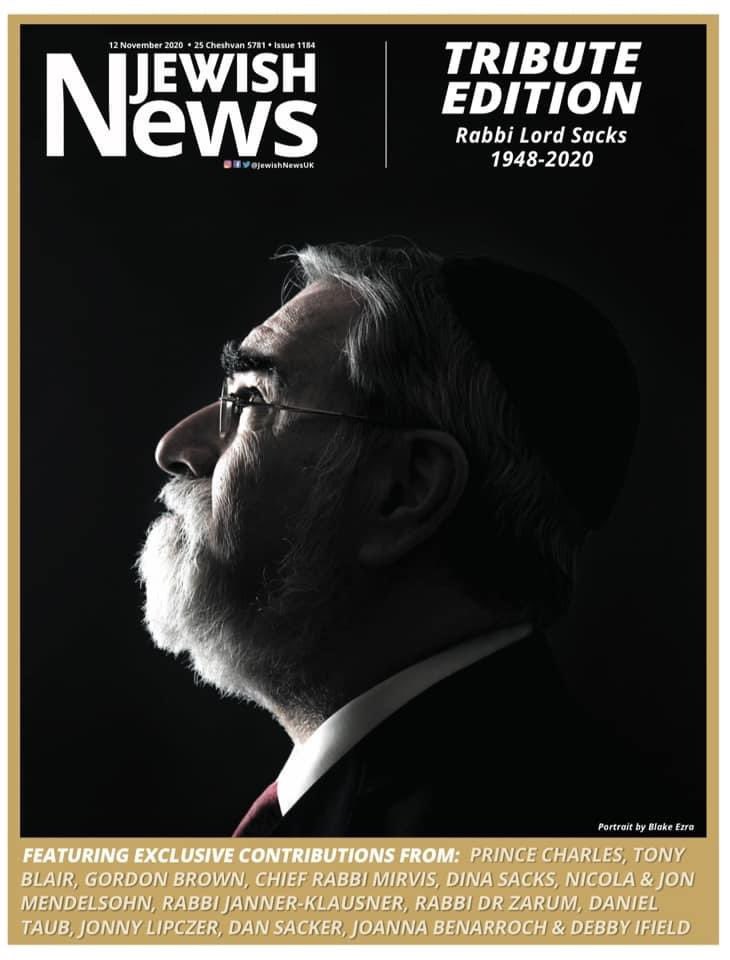

Prince Charles: I have lost a trusted guide, an inspired teacher and a friend

The death of Rabbi Lord Sacks is the most profound loss to the Jewish community, to this nation and to the world. Those who knew him through his writings, sermons and broadcasts will have lost a source of unfailing wisdom, sanity and moral conviction in often bewildering and confusing times.Remembering Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (1948-2020)

Those who, like myself, had the privilege of knowing him personally, have lost a trusted guide and an inspired teacher. I, for one, have lost a true and steadfast friend.

His family, most of all, have lost a great man whose devotion to them knew no bounds, and my heart goes out to them in their grief.

Over many years, I had come to value Rabbi Sacks’s counsel immensely. With his seemingly inexhaustible store of learning, his never-failing wisdom and his instinct for the power of the story in our lives, he could be relied upon to identify clearly the moral issues in question, and to define fearlessly the choices being faced.

The apparent ease with which he could cut through the confusion and clamour of our current concerns was grounded in his deep scholarship in both secular and religious disciplines, making him uniquely able to speak with conviction across boundaries of religion, culture and generations.

His life was distinguished by three commitments: commitment to listening to, and learning from, others without fear of compromising either his or their deeply held convictions; commitment to the institutions of the Nation which he nurtured through his own advocacy and participation; commitment to the integrity and harmony of God’s Creation, to Shalom.

Like so many young Jews, I first encountered Jonathan Sacks when I began asking serious questions about Judaism. At the time, he was the chief rabbi of a community an ocean away, but through his books—he would write dozens, at a pace of one per year—I had access to him as a high school student in New York.Nuance: The critical legacy of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks – opinion

I wasn’t the only one who did this. In college, a friend went to Harvard’s Widener Library, photocopied pages from the first edition of Sacks’ post-9/11 work The Dignity of Difference, and passed them around like contraband. (Rabbi Sacks’ expansive view of religious pluralism—and of the integrity of Christianity and Islam—had upset his ultra-Orthodox constituents at the time, and he subsequently gently revised the book to assuage them, even as he never abandoned his original position.) When he visited the states and spoke at MIT, many of us trekked across Cambridge to hear him.

For 22 years as chief rabbi, Sacks walked a tightrope as an Oxbridge-educated modern Orthodox rabbi tasked with representing a diverse Jewish community, both in official and unofficial capacity. As he wryly put it back in 1991, “There are many great Jewish leaders. There are very few great Jewish followers. So leading the Jewish people turns out to be very difficult.”

His tenure, however, was a success, spanning over two decades. In 2013, he surprised many by retiring as chief rabbi at age 65—not to recede from public life, but to pursue grander ambitions. That’s when I met him.

I interviewed Sacks for the first time shortly after he stepped down. I expected him to deftly sidestep some of my more pointed questions about politics and faith, but he surprised me by tackling most of them head-on. It soon became clear that this was one reason he had decided to depart his post. As he put it, “When you’re no longer captain of the team, you are much more able to express yourself as an individual.” Being freed from institutional constraints enabled him to reach and embrace broader parts of the Jewish community than he could when encumbered by the political sensitivities and geographic limitations of his office. He traveled the globe, taught at Yeshiva University and New York University, and made connections with Jews outside the Orthodox world—many of whom mourned his loss over the weekend.

But for all the tributes from people like me in the media, Sacks didn’t just talk to those with large platforms or celebrity. I know firsthand from friends how he emailed personally with students, elementary school teachers, and others who sought his guidance. I can only imagine the amount of correspondence he must have received, and cannot imagine how he managed to fit it into his schedule between his dozens of books, online videos, and speeches and media appearances around the globe.

RABBI SACKS taught us that this art of nuance and disagreeing agreeably goes beyond the realm of the American election. It applies to every area of life, and is desperately needed in the complex reality called the Jewish State of Israel.12 lessons I learned from Rabbi Sacks

One can vehemently disagree with the religious practice of others while also standing up for their right to choose their own theology; one can believe that all of Israel belongs to the Jewish people while also caring deeply for the well-being of the Palestinian people; one can live in a settlement while also firmly hoping and striving for peace that may require relinquishing that community; one can believe that Torah study is the highest value while also supporting military service for all; one can be against racism and discrimination while also calling out the failings of Israel’s Arab population and their elected leaders; one can be proudly Left wing and Zionist, and one can be strongly Right wing and open-minded; one can support Benjamin Netanyahu for prime minister without suggesting that Benny Gantz or Yair Lapid are horrific human beings, and vice versa; and we can learn much from the example of friendships such as that between the late minister Uri Orbach from the right-wing and religious Jewish Home Party and MK Ilan Gilon from the left-wing and secular Meretz Party, both of whom labeled each other as “best friends.”

“Diversity is a sign of strength not weakness,” Rabbi Sacks once wrote in Jewish Action. “As the Netziv writes in his commentary to the Tower of Babel, uniformity of thought is not a sign of freedom but its opposite.... So difference, argument, clashes of style and substance are signs not of unhealthy division but of health.”

Divisive and polarizing rhetoric are reaching destructive levels worldwide, to the point that democratic systems and decent civilizations are at risk of total collapse. As we mourn the passing of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, we must save the very foundations of civilized society by internalizing and putting into practice his lessons of nuance and tolerance.

When I was a post-graduate student at Yeshiva University, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks came as a visiting professor for the semester, teaching undergraduate students. Despite not being an undergraduate, I signed up. I knew this was an opportunity of once in a lifetime. Having listened to so many of his classes and adoring his teachings, I went to every class of his I could attend. From that semester, and following so many of his lectures, I found so many valuable lessons, speaking volumes of who he was, and giving me goals to aspire to. Here are some of them:The Tikvah Podcast: Daniel Gordis on America, Israel, and the Sources of Jewish Resilience

Education is everything- Rabbi Sacks loved children. His saying: "to defend a country, you need an army, to defend a civilization you need schools," resonated in Jewish day schools around the world. Rabbi Sacks was a brilliant intellectual, yet he made sure his works took the form of a family edition Covenant and Conversation for Shabbat dinners. Time and again, Rabbi Sacks spoke about Jewish education as the epicenter of our existence. Day schools, children, and Jewish education meant everything to him. History will record that day school enrollment in the United Kingdom during his tenure as chief rabbi has skyrocketed, something for which he gets a great deal of credit.

Love- Rabbi Sacks' life did not go on without controversy. He faced criticism from multiple directions. Yet those always fell by the wayside—not because Rabbi Sacks fought back or engaged in mudslinging or heavy debate; it was his way of love, kindness, and graciousness always prevailed. "When the Lord accepts a person's ways, He will cause even his enemies to make peace with him." (Proverbs 16). As Menachem Begin put it, "not in merit of power, but the power of merit." No attack on him was important enough for him to hit back at those who criticized him. No insult was a justification for self-defense.

I remember showing Rabbi Sacks' famous video "Why I am a Jew" to a group of Jewish 5th graders who did not study in a Jewish day school. The room was dark and quiet, and Rabbi Sacks' beautiful voice was resonating in the room. Suddenly one of the kids asked most innocently and beautifully: "Is that God speaking?" To carry the message of God, Rabbi Sacks radiated love, compassion, and care for every person; that is how he found his way to so many hearts.

I once came to Rabbi Sacks right before class with a book of his I had meant to give my grandmother for her birthday. I asked him if he can quickly autograph it if it was not a trouble. He asked what her name was and then went on to write her a beautiful and thoughtful note. Thoughts, wisdom, and ideas, can never go too far without the heart that comes with it. Rabbi Sacks embodied Eleanor Rosevelt's saying: "nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care." Even if you never met Rabbi Sacks, you knew he cared.

The year 2020 has been one of real suffering. The Coronavirus has infected tens of millions the world over and has taken the lives of a quarter of a million Americans. It’s decimated the economy, shuttered businesses, brought low great cities, and immiserated millions who could not even attend funerals or weddings, visit the sick, or console the demoralized. This podcast focuses on how to think Jewishly about suffering and about the sources of Jewish fortitude in the face of tragedy and challenge. In his October 2020 Mosaic essay, “How America’s Idealism Drained Its Jews of Their Resilience,” Shalem College’s Daniel Gordis examines recent experiences of Jewish suffering and how different Jewish communities responded to it. In doing so, he makes the case that Jewish tradition and Jewish nationalism endow the Jewish soul with the resources to persevere in the face of adversity. Liberal American Jewish communities, by contrast, have no such resources to draw upon. He joins Jonathan Silver to discuss his essay and more.