Phyllis Chesler: How I got canceled

Perhaps contemporary ‘cancel culture’ officially began in 1989, when Khomeini issued his fatwa against Salman Rushdie for having ‘defamed’ Islam in The Satanic Verses. Rushdie was ushered into hiding and the Islamist assault on truth-speech in the West was on. But here’s what I also think.Cancel culture - and the Jewish experience

The day after Israel won its 1967 war of self-defense, the propaganda began in deadly earnest against both Israel and the West. Within two decades, perhaps less, Western universities were intellectually and politically ‘occupied’ by Stalinist and Islamist narratives. Balkanized social identities and victimology ruled.

Academics, including feminists (my people), became more obsessed with the alleged occupation of Palestine, a country that had never existed, than with real genocides or the occupation of women’s bodies.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the intelligentsia passionately agreed that ‘Islamophobia’ really existed.

They were only a decade away from believing that men can be women; that only the West, not the Rest, has ever engaged in slavery, imperialism and colonialism; and that victims always trump victimizers, even when the victim is actually the aggressor.

Disagree with any of this, and you’re Out. History itself has been found guilty by this crowd and every effort is now underway, not only to judge it, but to disappear as much of it as possible.

Perhaps I’m something of a pioneer because I was first ‘canceled’ in 2002-03.

Please understand: I do not view myself as a victim for refusing to submit to politically correct speech codes or groupthink. I’m one of the lucky ones. Despite adversities, I’ve been writing for more than 50 years and I’m still at it.

Having chosen a life of ideas, I expected enlightened debate.

Another variant of cancel culture detailed in my book happened in the Netherlands. Professor Pieter van der Horst, a gentile, is an internationally known scholar specializing in early Christian and Jewish studies. On June 16, 2006, as he was concluding his academic teaching career at Utrecht University, he delivered a farewell lecture on the topic “The Myths of Jewish Cannibalism.” In the lecture he drew a line connecting the more than two millennia of classic pre-Christian Greek antisemitism to the anti-Jewish blood libel now popular in the Arab world.How Iran illustrates the fallacy of social-media censorship

On the day he gave the lecture, the Dutch Jewish weekly NIW claimed that his text had been severely censored by the university’s rector. Van der Horst later elaborated on this in an article entitled “Tying Down Academic Freedom” in the Wall Street Journal. In the piece, he said the Rector Magnificus of Utrecht University, a pharmacologist, had summoned him to appear before a committee that included three other professors. The committee and the rector told him along with others that his lecture damaged the university’s ability to build bridges between Muslims and non-Muslims.

The committee also claimed that the scholarly level of Van der Horst’s lecture was poor. This was a bizarre claim as he was a member of the Dutch Royal Academy, the pinnacle of Dutch scholarship. Later, his uncensored lecture was published as a book. It is a well-conceived text. What Van der Horst had wanted to say before the university’s censorship action was entirely true. If all Utrecht University’s lectures were on the same level, the institution could be proud.

In the last paragraph of the Harper’s letter, it says: “As writers we need a culture that leaves us room for experimentation, risk-taking and even mistakes.” This statement is old hat for defenders of Israel at the large number of universities where cancel culture has appeared. In light of the Jewish experience in this century, the Harper’s letter is an innocuous, inconclusive text.

Had the signatories of the letter thought more deeply about the issue they were writing about, they might have arrived at an operational conclusion. The text of the First Amendment of the US Constitution in its present form is obsolete. It should be reformulated to make incitement and hate speech punishable by law, as is the case in several other countries. Then, for instance, America’s leading antisemite, Louis Farrakhan, would be in jail rather than be flattered and quoted by people who don’t mind his anti-Jewish hate speech. If that amendment were changed, life might also become a little more comfortable for the signatories of the Harper’s letter.

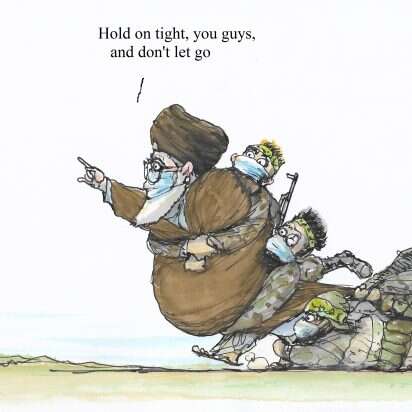

The problem with more censorship is that Twitter’s efforts, as well as the first steps down that road by Google and Facebook, show that it isn’t possible to ask these companies to merely do the decent thing and take down the likes of Louis Farrakhan and the genocidal theocrats running Iran.Lebanon protests, Macron visit highlight absurd EU policy on Hezbollah

Twitter has no more interest in addressing anti-Semitism than does Facebook. But what it is interested in doing is wielding its enormous power to advance the political agendas of its leaders and staff.

Trump tweets things that are off-base and sometimes not true. But the same can be said for many politicians. Trump is different in that he understood quicker than most that Twitter provided him with a way to reach voters without the filter that the media has employed in its traditional role as information gatekeeper. So it’s understandable if hardly justified that his media critics want to reassert their power. That’s why they have targeted Trump, whose policies and persona are despised by the left-leaning staff and ownership of social-media companies.

That pattern has characterized the actions of Google and Facebook in the past, which have targeted conservative publications and writers for the sort of treatment that has made them harder to find or read.

Should they choose more censorship, people like Khamenei have little to worry about. Twitter, and no doubt Facebook, will find a way to rationalize continuing to publish hate from oppressive governments lest they are shut out of large and potentially lucrative markets. Instead, they will not only do more to silence Trump and his supporters, but likely extend their scrutiny to Israel and its friends.

A company that thinks there’s an inimitable threat to civilization from a political opponent in the White House making comments that are merely controversial but finds Iran’s genocidal threats unexceptionable is simply incapable—regardless of what sorts of measures it puts in place to deal with the problem—of making rational or moral choices about whose voice to silence. And if they are going to play censor, then Trump and other Republicans are right to demand the abolition of Section 230 so they can have the same liability problems as other publishers instead of being simply cash machines with no accountability.

That should remind us why free people should always be wary of any idea that sets us off down a slippery slope towards censorship, especially when it relates to political ideas.

If there’s one thing we should have learned in recent months, it is that most people value their safety far more than their freedom. When it comes to giving up some of our autonomy to ensure public safety during a pandemic, that can be defensible. But when it comes to shutting up unpopular or even hateful ideas, then that’s a threat to everyone’s liberty. Given more encouragement to censor, Twitter and other such giants are more likely to target defenders of Israel than those who want to annihilate it. People generally only miss their freedom when it’s taken away from them. But if you think social-media companies can be trusted to do that to bad guys but leave the rest of us alone, then you haven’t been paying attention.

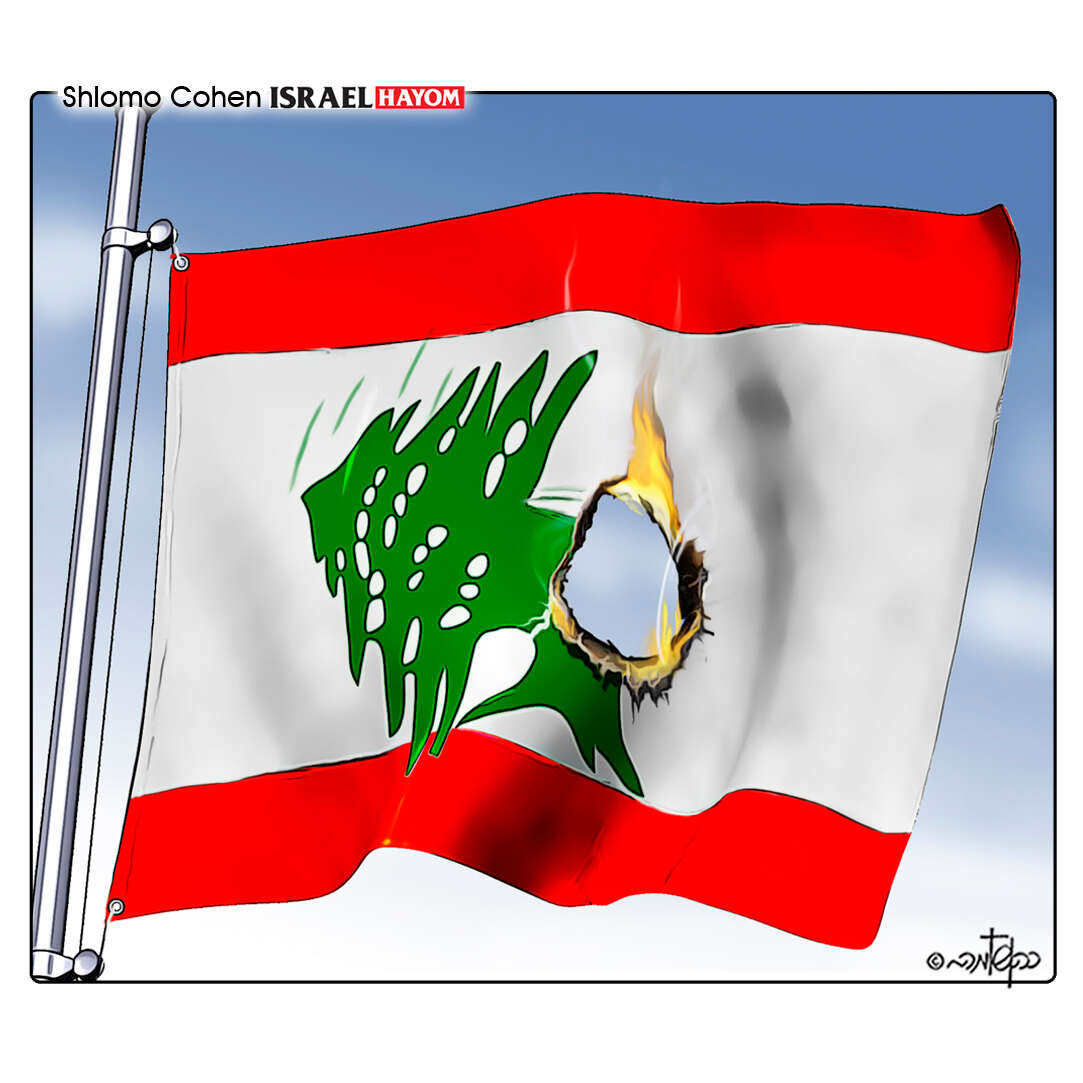

Watching the protests in Lebanon that rose after the massive explosion in Beirut last week, and seeing videos posted on social media by anguished and frustrated Lebanese people, a clear theme emerges: People are angry, and many of them are pointing fingers at Hezbollah.

Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shi’ite terrorist group, has held a firm grip over Lebanon’s governing coalition for years, even selecting Hassan Diab as prime minister in January. And as former ambassador to the UN Danny Danon told the Security Council last year, “the port of Beirut” – where last week’s deadly blast took place – “has become Hezbollah’s port,” used to transfer weapons and financially support the terrorist group as it develops advanced missiles.

Over the weekend, Lebanese demonstrators hung effigies of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, along with the political leaders who enable him, such as President Michel Aoun and Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri.

When French President Emmanuel Macron visited the site of the blast in Beirut’s port on Thursday – even as many of Lebanon’s political leaders avoided doing so – he was met with large crowds shouting “revolution” and “the people want the fall of the regime.” As he walked through a Christian district of Beirut, some shouted: “Mr. Macron, free us from Hezbollah.”

On the one hand, Hezbollah surely feels the heat from people who clearly have had enough of the destructive, creeping Iranian-backed takeover of their country. It’s not hard to connect these dots and view Hezbollah as a prime suspect at this point, if not of an intentional bombing, then of deadly negligence.

Nasrallah felt the need to make the laughable claim that Hezbollah “did not intervene in Lebanese affairs.”

In the same televised speech on Friday night, Nasrallah denied that Hezbollah controls the port, despite strong evidence to the contrary, or that it kept any explosives there. Hezbollah also kept large stockpiles of ammonium nitrate, the explosive responsible for the huge second blast in the Beirut port, in numerous locales in Europe until the Mossad helped the UK, Germany and Cyprus uncover them in recent years.