What Bibi wants to do in the West Bank is not annexation

Fifty-three years ago today, Israel was fighting for its survival. In a larger sense, that doesn’t make it all that different from any day in the preceding 19 years or the 53 that have followed. The Six-Day War was different, however, because it not only saw the tiny nation’s improbable victory over three Arab powers bent on its destruction, it returned vast swathes of the Land of Israel to Jewish custodianship. Two thousand years of history had been overturned in less than a week.Amb. Alan Baker: The U.S. Peace Plan, Political Wisdom and Double Standards

The legacy of this war is still debated today, because, in the words of Yossi Klein Halevi, victory ‘turned Israel into… history’s most improbable occupier’. Now we are told Israel is becoming an apartheid state — we’ve been told this for decades — because Benjamin Netanyahu is preparing to ‘annex the West Bank’. The UK’s Middle East Minister James Cleverly has denounced ‘annexation which we have consistently said we oppose — and which could be detrimental to a two-state solution’. Prominent British Jews have expressed ‘concern and alarm at the policy proposal to unilaterally annex areas of the West Bank’.

One problem: Israel isn’t preparing to annex the West Bank. I don’t mean in the sense that Haaretz’s Anshel Pfeffer has been warning: that Bibi has no intention of fulfilling his election promise. Bibi may well opt to keep the relative peace seen in the territories in recent years, but that’s not the issue. I’m not even pettifogging about the fact that the correct terminology is not ‘West Bank’ but Judea and Samaria. Though it is.

What Netanyahu has pledged to do is change the legal status of Israeli settlements as well as the Jordan Valley, a topographical buffer zone between Israel and Jordan. All in all, 30 per cent of Judea and Samaria would be governed in the same manner as the rest of Israel, leaving the remainder under a mixture of Israeli military administration and Palestinian civilian control.

This is not annexation. Under international law, annexation describes ‘the forcible acquisition of territory by one state at the expense of another’, and a) there is only one state involved in this dispute, b) since Israel already exercises a form of sovereignty over the territory in question, there would be no fresh acquisition, and c) the proposed changes would see the settlements and the Jordan Valley transfer from military to civilian law, the very opposite of the belligerence implicit in ‘forcible’.

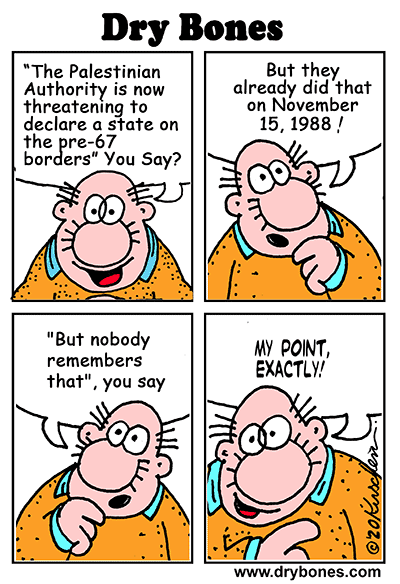

The Palestinian leadership's refusal to even consider the U.S. peace plan, despite the considerable political, economic and financial benefits that it offered them, threatens to undermine any possible return to genuine negotiations.Do Arab States Support a Palestinian State? Don’t Bet on It

Their refusal undermines the commitment by PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat in the name of the Palestinian people, in his September 9, 1993, letter to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, according to which: "The PLO commits itself to the Middle East peace process, and to a peaceful resolution of the conflict between the two sides, and declares that all outstanding issues relating to permanent status will be resolved through negotiations."

The Palestinian refusal should logically have generated considerable international condemnation of the Palestinian leadership. Yet the UN, the EU, international leaders and the international media have refrained from criticizing or condemning the Palestinian refusal to cooperate in a plan intended to restore peace negotiations. To the contrary, they encouraged the Palestinian leadership in its determination to undermine the plan.

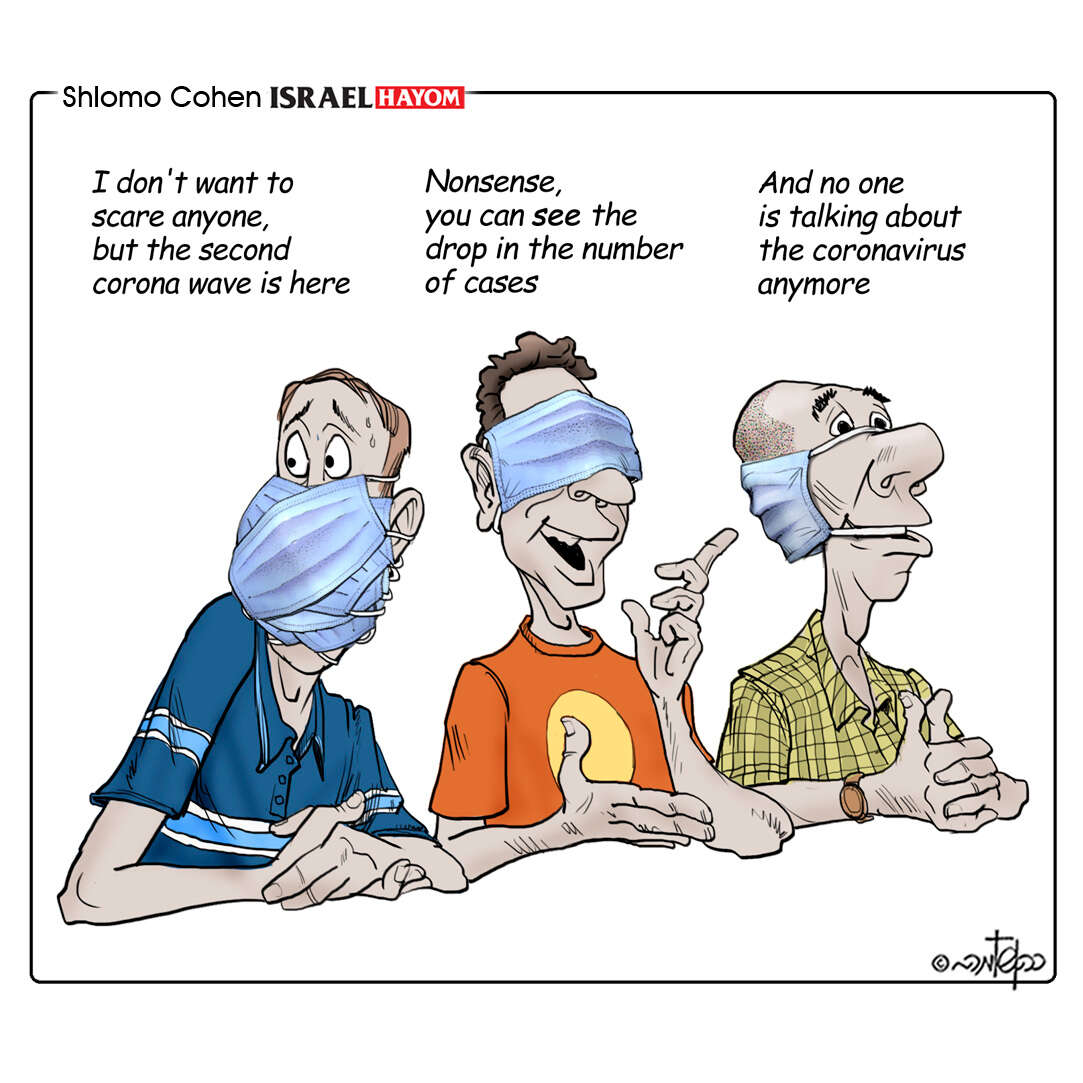

The international community and specifically the European states, after having turned a blind eye to the Palestinian boycott of the peace plan, are not really in the position to criticize and condemn Israel for considering ways to realize those components of the plan that are ultimately intended to apply to Israel.

The Palestinian leadership cannot exercise an indefinite right of veto over peace negotiations. Had they used political wisdom from the start and welcomed the plan as a basis for negotiation, then the issue of the unilateral application of sovereignty by Israel over parts of the West Bank would most likely not have arisen.

Why is the red carpet that welcomes Palestinian leaders to Western capitals exchanged for a shabby rug when they land in most Arab capitals?

In 2020, the widely-disseminated Arabic hashtag “Palestine is not my cause” reflects a growing Arab disdain toward Palestinian activism. It is consistent with the policy of key Arab leaders, which facilitated the successful conclusion of the 1979 Israel-Egypt peace negotiations by avoiding the myth of Palestinian centrality.

For example, Morocco’s King Hassan, who provided an essential tailwind to the initial stage of the peace negotiations, proclaimed: “The PLO is a cancer in the Arab body.” It is also compatible with a statement made by Egypt’s former President Anwar Sadat, a co-signer of the peace treaty: “Why would I want a Palestinian state? A Palestinian state would enhance the Soviet standing in the region and would join the radical Arab camp.”

This position was echoed by Hosni Mubarak, Sadat’s deputy, who succeeded him as president: “Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are not concerned about the Palestinians, and Jordan does not want a Palestinian state either … nor does Israel” (No More War, E. Ben Elissar, 1995, pp 106, 209, 207).

The tangible Arab walk — rather than the placating Arab talk — on the Palestinian issue reflects Arab contempt for the Palestinian track record, as well as the peripheral role played by the Palestinian issue in shaping the Middle East reality.

In 2020, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and all other pro-US Arab regimes are preoccupied with domestic and regional epicenters of subversion, terrorism, and conventional, ballistic, and nuclear threats, which significantly transcend the Palestinian issue.