Natan Sharansky with Gil Troy: The Doublethinkers

It was easy enough to remind myself and them who was really free and who is a scared doublethinker. All I had to do was tell some joke about the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev. Thank God, there were plenty of yarns about his arrogance, his crudeness, his senility. One kidded about him forcing Soviet cosmonauts to outdo the American astronauts who landed on the moon by rocketing to the sun, then reassuring them they wouldn’t be incinerated because they’d be launched during the night. As I’d tell my interrogators a joke, I’d laugh. And, as normal Soviet doublethinkers themselves, they would want to laugh. But they couldn’t, especially if two of them were there together. Laughter would end their careers.

So they’d covered up that temporary glint in their eyes with a tantrum. They’d pound the table, shouting, “HOW DARE YOU?”

“Look,” I’d say to them calmly, “you can’t even smile when you want to smile. And you claim that I’m in prison and you’re free?”

I did this to irritate them, because they spent so much time trying to irritate me. But, mainly, I was reminding myself that I was free, as long as I could laugh or cry in accordance with my own feelings.

Over the last three decades in freedom, I have noticed that—with apologies to Tolstoy—every dictatorship is oppressive in its own way, but the doublethinkers’ mental gymnastics are all alike. The feeling of release from the fear and giddy relief when crossing the line from doublethink to democratic dissent is also universal across cultures. This understanding prompted the Town Square Test I use to distinguish between free societies and fear societies: Can you express your individual views loudly, in public, without fear of being punished legally, formally, in any way? If yes, you live in a free society; if not, you’re in a fear society.

In the West today, the pressure to conform doesn’t come from the totalitarian top—our political leaders are not Stalinist dictators. Instead, it comes from the fanatics around us, in our neighborhoods, at school, at work, often using the prospect of Twitter-shaming to bully people into silence—or a fake, politically-correct compliance. Recent polls suggest that nearly two-thirds of Americans report self-censoring about politics at least occasionally, essentially becoming a nation of doublethinkers despite the magnificent constitutional protections for free thought and expression enshrined in the Bill of Rights

To preserve our integrity and our souls, the quality of our political debate and the creativity so essential to our cultural life, we need a Twitter Test challenging bottom-up cultural totalitarianism that is spreading throughout free societies. That test asks: In the democratic society in which you live, can you express your individual views loudly, in public and in private, on social media and at rallies, without fear of being shamed, excommunicated, or cancelled? Ultimately, whether you will live as a democratic doublethinker doesn’t depend on the authorities or on the corporations that run social media platforms: it depends on you. Each of us individually decides whether we want to submit to the crippling indignity of doublethink, or break the chains that keep us from expressing our own thoughts, and becoming whole.

#OnThisDay 1986, 'Prisoner of Zion' @NatanSharansky became a free man upon his release from Soviet gulag, where he spent 9 years!

— Arsen Ostrovsky (@Ostrov_A) February 11, 2021

As a fellow ‘Refusenik’, Natan Sharansky is a tremendous source of inspiration & personal hero of mine, the very epitome of a modern proud Zionist. pic.twitter.com/q5IZkLXNHG

Coffin Problems

Luck was a defining factor in determining the fate of many in the Soviet Union, and it is the common vein that unites the subjects of this story. Yet the stories recounted here are not representative. Such stories can never be completely told because the Soviet system intentionally left much undocumented. Critical marks on examinations were often written in erasable pencil. Written exams were eschewed in favor of oral ones. Some who lived through the period do not feel they have anything to add; others may find the experience too painful to contemplate, much less talk about. Even among the small cohort described here, there is consensus on a few things but not on many others.Eli Lake: America in the World: Sheltering in Place

Kac quit his job in 1976 and applied for an exit visa to Israel. He received permission to leave quickly. He secured a position immediately at MIT where he remains today. Zelmanov eventually secured a role at Novosibirsk State and left in 1990. For his breakthrough work on a century-old problem, he was awarded a Fields Medal in 1994—the mathematical equivalent of a Nobel Prize.

Eliashberg was less lucky. He became a refusenik after his visa request was denied in 1979. He had returned to Leningrad before applying, and was forced to support himself at various temporary jobs. This promising mathematician found himself working as a night watchman at a car garage in the city. One of his friends put his own career on the line in order to secure for Eliashberg a job in an accounting software company. He remained there until 1987, when he was finally able to leave the Soviet Union. He was not sure if he would be able to rehabilitate himself as a mathematician. But he succeeded. In the decades since, he has won many of the most prestigious awards in mathematics including the Veblen, Crafoord, and Wolf prizes. Today, he is on the mathematics faculty at Stanford.

For her part, Julia Rashba recalled a poignant moment in the elevator with the MGU examiner who had failed her on the entrance exam. In many ways, she felt unprepared for what had just happened to her. She had experienced anti-Semitism in her childhood with bullies and cruel taunts. Once, as a little girl, she ran away from a day camp where the bullying was too much. She was not aware that the sorts of anti-Semitism that lived in adult institutions would be less benign. She was raised, however, to believe that even in such a discriminatory system, where her own father had experienced nearly insurmountable travails to rise to the top of the Soviet physics establishment—that she needed only to work hard and act with integrity and things should work out.

They had not. The examination she “failed” was not even for medical school, it was for a chemistry program that offered some biomedical tracks. She had hoped that she could contribute to medicine as a scientific researcher, even if she would not be allowed to be a clinician. The system would not even allow this tenuous finger hold on her dream. She recalls that the examiner, perhaps seeking absolution for the shame of what he had just done, quietly apologized and asked for her forgiveness. She refused.

That exchange tells us a lot about the Quincy Institute. The think tank’s foreign policy agenda and arguments echo the anti-interventionism of the 1930s. Most of its scholars are more worried about the exaggeration of threats posed by America’s adversaries than the actual regimes doing the actual threatening. In May, for example, Rachel Esplin Odell, a Quincy fellow, complained that Senator Romney was overstating the threat of China’s military expansion and unfairly blaming the state for the outbreak of the coronavirus: “The great irony of China’s military modernization is that it was in large part a response to America’s own grand strategy of military domination after the Cold War.” In this, of course, it resembled most everything else.

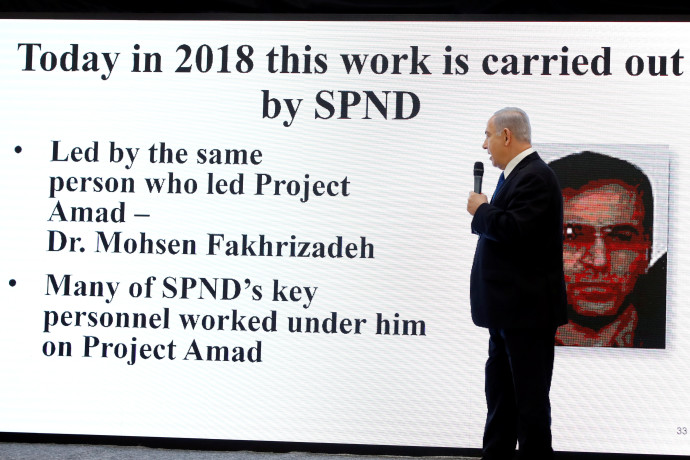

The institute has hired staff that come out of the anti-neoconservative movement of the 2000s. Here we come to a delicate matter. The anti-neoconservatives of that era flirted with and at times embraced an IR sort of anti-Semitism: the obsession with Israel and its influence on American statecraft. Like the America Firsters, the anti-neoconservatives worry about the power of a special interest — the Jewish one — dragging the country into another war. A few examples will suffice. In 2018, Eli Clifton, the director of Quincy’s “democratizing foreign policy” program, wrote a post for the blog of Jim Lobe, the editor of the institute’s journal Responsible Statecraft, that three Jewish billionaires — Sheldon Adelson, Bernard Marcus, and Paul Singer — “paved the way” for Trump’s decision to withdraw from Obama’s Iran nuclear deal through their generous political donations. It is certainly fair to report on the influence of money in politics, but given Trump’s well-known contempt for the Iran deal, Clifton’s formulation had an odor of something darker.

Then there is Trita Parsi, the institute’s Swedish-Iranian vice president, who is best known as the founder of the National Iranian American Council, a group that purports to be a non-partisan advocacy group for Iranian-Americans but has largely focused on softening American policy towards Iran. In 2015, as the Obama administration was rushing to finish the nuclear deal with Iran, his organization took out an ad in the New York Times that asked, “Will Congress side with our president or a foreign leader?” a reference to an upcoming speech before Congress by the Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The National Iranian American Council’s foray into the dual loyalty canard is ironic considering that Parsi himself has been a go-between for journalists and members of Congress who seek access to Mohammad Javad Zarif, Iran’s foreign minister.

This obsession with Israeli influence in American foreign policy is a long-standing concern for a segment of foreign policy realists, who believe that states get into trouble when the national interest is distorted by domestic politics — an affliction that is particularly acute in democratic societies which respect the rights of citizens to make their arguments to the public and to petition the government and to form lobbies. The most controversial of the realists’ scapegoating of the domestic determinants of foreign policy was an essay by Stephen Walt and John J. Mearsheimer (both Quincy fellows) that appeared in the London Review of Books in 2005. It argued that American foreign policy in the Middle East has been essentially captured by groups that seek to advance Israel’s national interest at the expense of America’s. “The thrust of US policy in the region derives almost entirely from domestic politics, and especially the activities of the ‘Israel Lobby,’” they wrote. “Other special-interest groups have managed to skew foreign policy, but no lobby has managed to divert it as far from what the national interest would suggest, while simultaneously convincing Americans that US interests and those of the other country — in this case, Israel — are essentially identical.”

Walt and Mearsheimer backed away from the most toxic elements of their essay in a subsequent book. The essay sought to explain the Iraq War as an outgrowth of the Israel lobby’s distortion of American foreign policy. The book made a more modest claim about the role it plays in increasing the annual military subsidy to Israel and stoking American bellicosity to Israel’s rivals like Iran. They also took pains to denounce anti-Semitism and acknowledge how Jewish Americans are particularly sensitive to arguments that present their organized political activity as undermining the national interest. Good for them. But the really important point is that events have discredited their claims. The all-powerful “Israel Lobby” was unable to wield its political influence to win the fight against Obama’s Iran deal. It was not able to stop Obama’s public pressuring of Israel to accept a settlement freeze. Decades earlier, it had not been able to thwart Reagan’s sale of AWACs to the Saudis. Anyone who believes in an omnipotent AIPAC is looking for conspiracies.

Impeachment, Matt Duss, what’s going on at the New York Times, the UN Human Rights Council, the ICC & Jerusalem. Our guest: ?@elianayjohnson?. Our best episode yet? You decide. Subscribe to ?@JIPodcast?. https://t.co/5JJ3Gln09D

— Richard Goldberg (@rich_goldberg) February 11, 2021