Noah Rothman: How Trump Can Avoid Obama’s Terror Trap

Obama’s impulse to dismiss the threat posed by Islamist insurgents in the wake of bin Laden’s death explains why he was so quick to dismiss the first wave of ISIS terrorists even as they sacked Iraqi cities. “The analogy we use around here sometimes,” the former president told the New Yorker’s David Remnick, “is if a jayvee team puts on Lakers uniforms that doesn’t make them Kobe Bryant.” Obama’s commitment to this narrative applied not only politically but in terms of policy, too. Though he conceded that “terrorism” remained a threat to the American homeland in a May 2014 address to cadets at West Point, the former president also claimed that the terror threat could not be alleviated by military means alone. “A strategy that involves invading every country that harbors terrorist networks is naïve and unsustainable,” the president insisted. By the end of the year, though, ISIS would have conquered vast swaths of territory in the Middle East, and American troops and airpower would again be unleashed on targets in both Iraq and Syria.Missing The Point Of The Latest Middle East Protests

And though Obama would eventually acknowledge his failure to anticipate ISIS’s rise or to develop a comprehensive strategy to combat it, his administration still stubbornly refused to acknowledge the obvious when it came to radical Islamist terror. As late as the summer of 2016, following the massacre at a gay nightclub in Orlando, administration officials made a concerted effort to “shift the conversation more to hate and not just terrorism,” according to CBS News reporter Paula Reid. Indeed, it’s hard to explain why the Justice Department scrubbed references to ISIS and al-Baghdadi in the transcript of the shooter’s confessional 911 call in the absence of a directive aimed at minimizing the revivified Islamist terror threat.

Like his predecessor, Donald Trump seems committed to the idea that ISIS has been “decimated” and can no longer recruit foreign fighters or effectively export terrorism. He’s been saying as much since February, and the death of ISIS’s chief executive will only make that narrative more irresistible. The evidence that Trump has begun to believe his own hype is not hard to come by. Experts have warned that the abrupt withdrawal of U.S. forces from forward positions in Syria would sow the seeds for an ISIS resurgence at least since Trump began to flirt with the prospect last December. If anything, those expert analyses underestimated the humanitarian and strategic setbacks that would follow such a withdrawal. American military and diplomatic officials appear clear-eyed about the potential for an ISIS comeback, but the president remains far more sanguine about the Islamist terrorist threat than his subordinates.

The dispatching of al-Baghdadi is a welcome development, but it does not make up for the strategic initiative sacrificed in the lead-up to this weekend’s successful operation. Today, as American special forces reportedly retake Syrian positions they’d abandoned only weeks or days earlier, U.S. positions in eastern Syria are reinforced with mechanized forces, and the State Department rallies a Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS in anticipation of the worst, it would behoove Trump to internalize a lesson his predecessor learned too late. He’d do well to hedge his bets.

In Lebanon and in Iraq, millennials have taken to the streets to protest their respective governments. It stands to reason — in both countries, services are minimal, jobs are non-existent, and the best way to make a living is to leave. Garbage piles up in the streets of Beirut and forest fires have decimated the country. In Iraq, corruption is endemic. But in both countries, there is more afoot.The strategic utility of mocking Abu Bakr al Baghdadi

The demonstrators, representing a variety of religious and ethnic groups in countries that have been wracked by sectarian fighting, are in agreement that the presence of Iran and its proxies in their homelands has deformed politics and economics alike.

Young people want Iran out.

Association with the Islamic Republic means that assets are taken and used by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, not by the civilian government, and it means religious and ethnic tensions are stoked to ensure that a unified public cannot impede Iran’s regional ambitions. Iran wants Iraq for the oil and also for the passageway through Sunni territory to Syria, Lebanon, and the Mediterranean Sea. It helped create the instability of ISIS in Iraq by “offering” to help contain the threat via Shiite militias commanded by Iranian officers. Those Shiite militias remain in the largely Sunni western part of Iraq and in the Kurdish areas.

The story in Lebanon goes back farther — to the early days of the Islamic Republic. Iran created Hezbollah and had its hand in the 1982 Marine barracks bombing that killed 244 Americans. It fostered and enlarged Hezbollah and planted an arsenal of rockets and missiles in southern Lebanon (in violation of U.N. Resolution 1701) and missile factories closer to Beirut. Lebanese civilians live between the Iranian/Hezbollah arsenal and potential Israeli retaliation if that arsenal is used.

Permanent revolution, permanent warfare, permanent upheaval — stoked by an outside force — makes it impossible to create the workable, modern, growing economy millennials demand; particularly in Lebanon, where there is a well-educated generation that crosses sectarian divides.

Announcing ISIS leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi's death, President Trump didn't hold back on Sunday. Baghdadi, Trump said, "died after running into a dead-end tunnel, whimpering and crying and screaming all the way."

That was only the first of a number of insults Trump lobbed at Baghdadi and the Islamic State during his speech. But while some are condemning the president's rhetoric, I believe it was both morally justified and strategically valuable.

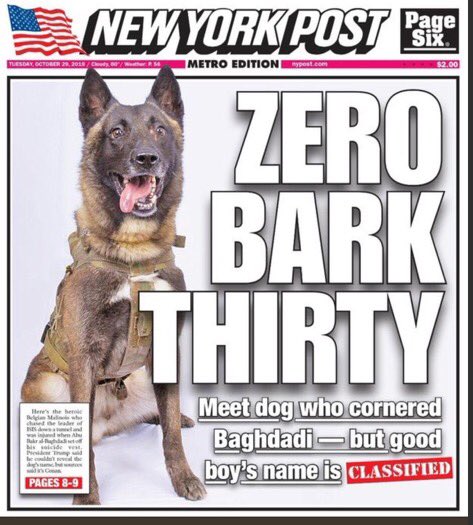

Although it might appear that Trump was resorting to standard-fare rhetorical excesses, the president seems to have intended his words to carry a broader strategic effect here. Note, for example, Trump's repeated focus on dogs, an animal regarded by most Islamic teachings as unclean and unworthy of companionship. Describing Baghdadi's desperate attempt to escape, Trump noted how "our dogs chased him down." Trump later observed that many ISIS fighters are "very frightened puppies" and concluded by saying that Baghdadi "died like a dog — he died like a coward."

This canine focus is extremely odd unless it is intentional, which I suspect it is. And that would be a good thing. ISIS presents itself as the holiest citadel of warriors, as a group serving God's pure and ordained will on Earth. But when the leader of ISIS's most hated adversary mocks its deceased caliph (emperor) as a fool who ran into a dead-end tunnel while being chased by lowly dogs, it erodes ISIS's credibility. It underscores how the organization, which at one point nearly qualified for its own seat at the United Nations, is now perceived as a sad joke.

.jpg)