Avraham David Moses was murdered on the eve of what is

considered to be the happiest month in the Jewish calendar, Rosh Chodesh Adar. In the secular

calendar, it was March 6, 2008, and Rivkah Moriah and her former husband David

were preparing for a class to be given that evening by Rav Aharon Lichtenstein in celebration of the 40th anniversary of Yeshivat Har Etzion. As the couple

gathered source materials for the lecture, Rivkah received the first text

message: “Attack in Mercaz HaRav, three moderately injured.”

We are used to these moments, here in Israel. Most of the

time, our loved ones were nowhere near the scene of the attack, had left there

hours before, or had just left and were only a block away and could hear the

explosion and see the smoke. So we have learned not to get too excited when we

hear of an attack on the news. We have learned to stay calm, to phone loved

ones, and touch base.

That’s what happens most of the time. But that was not what happened to Rivkah Moriah and her son Avraham David. There was an attack,

she tried to reach both Avraham David and his study partner, and all of her calls went

unanswered.

Her calls went unanswered because her 16-year-old son and

firstborn was murdered while studying Torah in a seminary study hall. Along

with his study partner, Segev.

***

When I heard, I thought about running into Rivkah at the grocery store, just three years earlier. Her cart had been filled with ingredients to make lasagna for a crowd. She was preparing for

Avraham David’s bar mitzvah. You could see how happy she was, it was in her

eyes. He was her firstborn.

|

| Rivkah and a very young Avraham David, her firstborn |

And now, three years later, Rivkah was preparing to see her son buried,

a good boy, a studious boy. A boy who was murdered while learning Torah.

How could a mother bear it? The short answer is no one

could.

It is now 14 years since Rivkah Moriah became an “angel

mom.” That’s a long time, almost as long as her Avraham David’s short life. And still,

from my lucky distance, I can see the lasting impact, the sadness and the pain.

|

| Blood-stained holy book at the scene of the Mercaz HaRav Massacre |

Since it is Adar I have been thinking about this. I always

think about Rivkah Moriah and her son Avraham David Moses in Adar. Adar is the

happiest month of the Jewish year. It's the month of Purim, the month I got married, but it is also

the month Avraham David Moses was murdered and his mother’s life

changed forever.

I don’t want to forget that. I don’t think any of us should.

We need to remember a boy who was murdered because he was a Jew, and the

suffering of the family he left behind.

|

| Avraham David with his little brothers, Noam and Chai. |

No special wisdom is necessary to notice that parents

don’t simply “bounce back” after their children are murdered by terrorists, lo aleinu [1].

That much we can see with our eyes. We wish we could help them, but there

is not all that much we can do. They are in it, and we are not.

Note: Words or phrases followed by bracketed numbers (e.g., [1], [2]) have translations or explanations listed at the end of this article.

And still, there are two things we can do:

1.

We can listen when grieving parents have

something to say, and respect the enormity of their experience.

2.

We can offer them opportunities to speak about

their children and say their names, so we’ll remember them, too.

It was with these two thoughts in mind that I asked Rivkah if she would consent to an interview to explore her feelings and to talk about her son, Avraham David, HY”D.[2]

She gracefully agreed.

Varda Epstein: Can you describe for those unfamiliar with the Mercaz HaRav Massacre what happened that day?

|

| Rivkah Moriah, today. |

Rivkah Moriah: Avraham

David was in tenth grade at the Yeshiva laTzeirim (Yashlatz), the yeshiva

high school that is adjacent to and shares a campus with Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav.

It was Thursday night and the first night of Rosh Chodesh Adar[3]

and seder erev[4]

had been early, so that the boys could set up the beit midrash[5]

for singing and dancing to celebrate. Yashlatz celebrates every Rosh Chodesh, but the celebration of Rosh Chodesh Adar was known to be

particularly festive. Groups of boys from other high schools were gathering to

come join them.

While some boys were setting up the beit midrash, and others were involved with organizing

refreshments, some of the most studious boys went over to the library at Mercaz

HaRav to continue their learning.

It was a very warm evening, the first warm evening of the

spring, and there were also groups of people in the yeshiva courtyard, enjoying

the weather and unwinding after a long week in the study hall.

The attacker was seen carrying a large box into the courtyard from outside the compound. This box contained a Kalashnikov, approximately 900 rounds of ammunition, and two pistols. He opened fire in the courtyard, then entered the stairwell, where he shot a young man on his way to study. The attacker then went back out to the courtyard and entered the library, where he methodically shot those who were trapped and unable to escape.

The attacker was neutralized by an adult yeshiva student,

Yitzchak Dadon, and an officer from the IDF who was at home on leave in the

neighborhood, David Shapiro. It was all over in fifteen minutes, but not before

eight boys and young men were murdered, several more were critically injured,

and more were moderately injured while escaping. And those are just the

physical injuries.

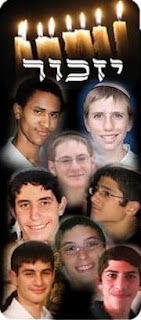

Neria Cohen 15

Segev Peniel Avichail 15

Yonatan Eldar 16

Avraham David Moses 16

Yochai Lifshitz 18

Yonadav Hirshfeld 18

Ro’ee Aharon Rot 18

Doron Maharate 26

Varda Epstein: What

was it like in the early days, after the shiva

was over? What was it like waking up in the morning and just getting

through the days? How long was it before you found a way forward?

Rivkah Moriah: There was heavy shock. I only understood how

much afterwards. It’s like when you’re traveling in heavy fog, and you can see

what's right in front of you, but nothing else. I didn’t even see how much I

couldn’t see. I was lucky to have a friend who used the phrase Person Bearing

Great Sadness, and she helped me understand that what I most needed help with

was getting the children out in the mornings. She came by every single morning

till the end of the school year and then for another school year. At first she

brought the sandwiches, and then she helped while I got the kids ready and made

sandwiches.

At first, if each of my kids got to their educational

framework for any part of a day, it was a good day. There were sandwiches for

school, and a lot of cereal for supper. For a year, what I could manage for

supper was what my friends brought or cereal. My success was that, during that

time, we never ran out of cereal or milk. After a while, I’m not sure when, I

started cooking pasta or ready-formed hamburger patties.

September 2010 – two and a half years later – I started

opening envelopes again. The bills and everything else that was urgent had been

taken care of by David, and a lot of other things just got put in a pile that

was 2 1/2 years deep. Because mail is dated, it was the clear and obvious

measure of when I came out of the fog.

Varda Epstein: What

about the family? How did the terror attack—the sudden, violent murder of your

son—affect his siblings?

The death of a sibling is highly traumatic. Not only did my

kids and step kids lose a brother, but their own vulnerability was also

heightened. I like to say that, when an individual family member has a crisis,

ideally the rest of the family would come together to support them. When there

is a family crisis, every single one of the family members’ functioning is

compromised. Some of what was hard for my kids was that Mom was having such a

hard time.

Varda Epstein: What

are the lingering effects of a terror attack and brutal loss of a son and

sibling? Do any of you suffer PTSD? Is there something that helps to mitigate

the symptoms?

Rivkah Moriah: A shattering loss like this has pervasive

influence. While PTSD has a formal definition that requires an official

diagnosis, I can definitely say that there was trauma, and there is

post-traumatic stress. There is also something called Traumatic Bereavement.

I have been lucky to have found a gifted therapist at the One Family Foundation. My children’s

trauma has also been mitigated by the wonderful children’s programs and summer

camps of the One Family Foundation and the Koby Mandell Foundation.

While, after fourteen years, there are many ways that we

have adjusted to losing Avraham David, it is still, in some ways, an unfolding

story.

I appreciate that the discussion of trauma is becoming

acceptable in Israeli society. While some people are graced with post-traumatic

growth, this is certainly not a given.

A trauma like surviving a school shooting can be

unintentionally dwarfed by death or the grief of first-degree relatives. This

concerns me. The students who were there and lived through it, and even those

who weren't on campus but whose school was breeched and whose friends were

murdered participated in comforting the families at the shiva and have continued to have done so at memorials over the

years. They no doubt had and still have their own issues to deal with.

I hope that the shift towards increasing resources for those

who have experienced trauma continues. It would be appropriate if we develop a

better understanding of the grief and trauma of people in this position, so

that they can be better supported, and not just be in a position where they are

expected to give support.

Varda Epstein: Why do

you think Avraham David was murdered while he was learning Torah? What is the

significance of that for his legacy? What does it feel like to be the mother of

a son who died Al Kidush Hashem[6]?

Rivkah Moriah: We may not realize it, but we need people who die Al Kiddush Hashem to strengthen our faith, for our faith is a kind of security. As he died his martyr’s death, Rabbi Akiva

lengthened the recitation of G-d's unity in the Shema[7].

Rebbe Tarfon spoke of letters he saw flying in the air.

Many stories have been told about Avraham David and the

other seven boys and young men who were killed in the massacre, and I think

it’s right to honor their memories and grow in our faith with the retelling.

According to tradition, it is considered a privilege to die Al Kiddush Hashem. I think there are

very profound and holy reasons for this idea, and it has really helped me.

Nevertheless, as Avraham David’s mother, and because of who

I am, I also think of the rakes that tore Rabbi Akiva’s flesh, the fire and

smoke that engulfed Rebbe Tarfon, and the fear and pain with which Avraham

David died.

|

| Blood-stained prayer shawls at the scene of the Mercaz HaRav Massacre |

Varda Epstein: How

have you tried to keep the memory of Avraham David alive for your family and

for the world? Are you in touch with his fellow students or teachers? How does

the yeshiva memorialize the attack?

Rivkah Moriah: Avraham David is very much part of our world.

The nature of his presence and memory has changed over the years. For a while,

I had to protect some of the younger kids from hearing about it too much.

There are kids in the family who don’t have memories of

Avraham David. This needs to be navigated in a way that honors what has been

hard and painful in their lives and helps them know the story that is their own story, without overwriting it with one’s

own story.

Yashlatz has memorials that are suited to their students,

which are very comforting to me having lost someone of high school age.

Mercaz has memorials that are appropriate to their own students.

With very few exceptions, Rav Yerachmiel Weiss, the Rosh Yeshiva [8]

of Yashlatz at the time of the attack, has called every single erev shabbat and chag [9]

for fourteen years. There are a few classmates who have maintained a close

friendship with us, and many who participate in memorials.

|

| Grave of Avraham David Moses, HY"D. Murdered at age 16. |

Varda Epstein: Talk

to us about the contradiction of murder on the eve of the happiest month of the

year, Adar. How do you handle that?

Do you work on finding joy at that time, or is that just too difficult? How

does the yeshiva handle a memorial like that on Rosh Chodesh Adar in a way that also honors the significance of

that month, and the emotions we are intended to feel?

Rivkah Moriah: I’m letting this one simmer for me. I grapple

with this every year, and I grapple with it in a more general way in an ongoing

way. I’m beginning to accept that maybe the injunction is different for me.

A person who mustn’t eat gluten is exempt from the specific mitzva [10]

of lechem mishneh[11]

on Shabbat. Rosh Chodesh Adar is the very saddest day of the year for me, so

there is a bit of a disjunct for me at this season. I am lucky to daven [12]

in a minyan [13]

that does not to sing Mishemishe [14]

… when bentching Adar[15],

purely for my sake. This kindness, and the kindness of others at this season,

is my nechamah [16],

which is akin to simchah [17].

Varda Epstein: What

do you think Avraham David would be doing today, had he lived to fulfill his

potential?

|

| Avraham David Moses, HY"D |

Rivkah Moriah: If he had continued on the path he had begun,

he would have become a scholar. I have been told that his depth and breadth of

scholarship was extraordinary for a teenager. This was one of the great losses

to the Nation [18].

Avraham David wanted to marry young, and he had put great effort into refining

his character. I would have loved to have seen him as a husband and as a

father.

Varda Epstein: What can

we, the Jewish people, learn from Avraham David Moses, HY”D? What can we learn

from what happened to him?

Rivkah Moriah: Avraham David was very intensely Avraham David. While we can perhaps be inspired by him to pray or learn or perform mitzvot [19] with more intention, I think he can best inspire us to be more authentically who we ourselves are.

While I think many things could be learned from Avraham David’s death, and how he died, something I have learned is so subtle yet profound that I have to keep learning it over and over. This piece opens with why you want to write it. About the enormity of my loss. About opportunities to say Avraham David’s name. And that in a very real way, it is also your loss.

It is in this meeting-place, much more than a specific thing one could say, that nechama takes place.

Note to the reader: This was a difficult interview to conduct. I found myself afraid to ask the questions I wanted to ask. Afraid to pry. Afraid to cause further pain and hurt.

Perhaps it's because I know Rivkah personally, or perhaps because this time, the someone who lost someone is a mother, and the son she lost, died al Kiddush Hashem. For whatever reason, throughout the process of creating this interview, I felt like I was stepping into some kind of sacred realm and I wasn't sure I had the right to be there.

And it is an unspeakable crime that Avraham David is lost to her until the final redemption.

[1]

Prayerful phrase that roughly means: “May it not happen to us.”

[2]

Abbreviation for “Hashem Yinkom Damo.” When we speak of the dead, we normally

say Olav/Aleha hashalom” May s/he rest in peace. But for martyrs, we say “May

God avenge his blood.”

[3]

beginning of the lunar month of Adar

[4]

evening learning session

[5]

study hall

[6] A

death that sanctifies God’s name, for instance a boy murdered while studying

God’s holy Torah, as is the case with Avraham David.

[7]

The prayer that affirms belief in one God. The prayer is recited three times

daily and also when someone is dying.

[8]

Yeshiva head, a principal who is also a rabbi.

[9]

Erev Shabbat and Chag (Sabbath and holiday eve, in this case, the approach of

these holidays, before they actually begin.)

[10]

Commandment

[11]

We put out two loaves of bread to commemorate the double portion of manna we

received in the dessert on the Sabbath.

[12]

Pray (Yiddish)

[13]

Quorum for prayer, congregation

[14]

Traditional song for month of Adar. The Hebrew lyrics of the song mean: “Who

that ushers in the month of Adar, increases joy.”

[15] Praying

in the month of Adar

[16]

Comfort

[17]

Happiness

[18]

The Jewish people.

[19]

Commandments, plural of mitzvah.