I slid off the chair to the floor, but I know nothing of

this. I am gone. Only later do I ask Dov, my husband, how it happened. “Slid”

was his word. “You slid off the chair onto the floor,” said Dov.

“Did I hit my head?”

“No, the medics kind of caught you and eased you down to the

floor.”

“Then what happened?”

“The MDA guy immediately started compressions,” says Dov, with some awe in his voice. He is obviously impressed with the grace and speed

with which this impromptu team of medics sprang into action.

I chew this over for a few days, this scenario, as

described to me by my husband.

Slowly more questions occur. “What did I look like?”

“You were white,” his voice catches.

I hear that it is too difficult for him to speak about

it—he had watched me die. Still, I have to ask. “Like all-over white? Were my

lips white?”

“You were completely white,” he says.

I take mercy on him and table my questions. For now.

As for what I remember, it was this. I knew nothing. Not a

thing. And then I was aware of blackness, and slowly color came, pixelated at

first, and stole over the blackness and I heard, “Varda, Varda!” my husband’s

voice, and the medics’ voices, and someone was slapping my face, and the MDA

guy said. “Varda, your heart stopped for two seconds. You are going to the

hospital.”

“No, no. I don’t want to go.”

Basically, at this point, I was not compos mentis. I think I

hadn’t been for much of the time the medics were with me, because if it had

really been a money thing—my mind would have long been at rest. The medics

called MDA in spite of me, which already meant I was off the hook for payment.

And now that my heart had stopped, there was no way I would not be admitted,

which meant I would not have to pay for an ER visit. It is therefore impossible

for me to explain the true reasons for why I continued to protest. “Is it about

the money, or something else?” asked the MDA guy as I continued to protest.

“It’s the money . . .” I said.

“Ah ha! Varda,” said the MDA guy,” you are not going to have

to pay. Your heart stopped.”

“. . . and my

husband,” I said, in a feeble voice. “He needs me to take care of him,” but no

one heard me. They were too busy strapping me onto a stretcher in preparation

to take me out of our apartment for transport in the ambulance.

“I’m sorry. I’m so heavy,” I said, embarrassed.

“You’re not so heavy,” said the MDA guy.

As they take me out of the apartment, I see the sky is no longer dark, as it

had been when I awoke that morning. More embarrassment, thinking of the

neighbors on our quiet street, waking up to the ruckus of medics loading

someone in crisis (me) into an ambulance. I feel bad to be the cause of this

too early, too noisy, rude awakening.

I am in the ambulance, and as we drive away, I feel as

though I am flailing from side to side, unmoored. “But how will I keep from

falling?” I say aloud.

“Don’t worry,” says Elisheva the medic, who is also my

friend. “We strapped you in very well. You can’t fall.”

It didn’t feel like it. I didn’t feel the straps, but I

trust Elisheva. There is no place to look but up, so I do. I am looking at the

interior of the roof of the ambulance. Everything is as if in brownout. Then

suddenly the brown lifts away and the “ceiling” looks bright white. “I feel

better!” I cry out.

Elisheva says, “Good, good!” encouraging me. Then the

brownout returns. This happens several times. Each time the foggy, beigey brown

clears to white, I say, “I feel better!” surprised. Relieved.

Each time, Elisheva says, “Good!”

At some point during the ride to the hospital, I wonder why

this is happening to me. And then I know. It is October 7. It is the atrocities, the

war, the ongoing situation with the hostages. I lift my head and look at

Elisheva, “The hostages,” I cry to her, knowing she will feel me. “I can’t

bear it,” I say and both she and the MDA guy look at me, and the brownout comes

once more.

It was the most alive I had felt since this whole thing

began. And I knew that what I had promised would not happen, had happened.

At the start of the war I had said to myself, “I will not let Hamas break me,”

and now it had. I had broken. It had been too much for me. I was human, flesh

and blood. It was too much for a body to bear and not be overcome. I had

suppressed it too much. Had tried to, anyway.

I had vowed not to write about the atrocities, not to play

the poor us card before the world. I talked “around” the harshness, the

hideousness of Hamas and what they had done and continue to do, in my columns. I

wrote about rape fear, rather than rape. I wrote about Gazan support for Hamas;

the “ceasefire deal with the devil;” the dirty money trail that led to October

7th; the fickleness of Joe Biden in regard to his (non)support for

Israel; and so on and so forth. Anything but to talk about women raped until

finally dead, their legs that could not be closed, but stood at odd angles, broken.

Raped front and back, the men, too. Women raped in front of their husbands,

husbands raped in front of their wives. Daughters, sisters, children in front

of parents, in front of each other. Sights and sounds that would haunt the

survivors, the few of them that remained, forever.

I vowed not to write about any of this, even as it ate me

from inside. I knew it was eating me from inside. But it was not fair for me to

be feeling this. I was not the one suffering. The suffering belonged to the

raped, the murdered, the decapitated—those who could no longer feel, and those

who felt still, wherever they were, in the depths of some tunnel suffering

unimaginable horrors.

I remember the day I heard about Hamas baking a baby in an

oven. I was in the car with my husband when I read it on X, and I cried out.

“What?” asked my husband.

But I could not tell him. First because I was too consumed

with the pain, the thought of the baby and what it experienced, and then

because I knew it was too upsetting to share. It was something that was new to

me. It had obviously just come to light. I didn’t want anyone else to have to

know this—to have to live with this knowledge of the baby, in the oven, and

what it experienced. Even now, I can’t write about it without crying.

I moaned and cried in the car the whole way home, telling my

husband, “You don’t want to know. It’s too awful. It’s too awful.”

He understood I had heard about an atrocity just come to

light and he said I was right. He didn’t want to know. So I moaned and wailed the whole way home. I couldn’t stop. I cried about this on and off for days.

Couldn’t, shouldn’t wipe it out of my mind, and it ate away at me and ate away

at me. But I did not deserve to have this pain, I thought. It wasn’t about me,

but about the victims. I had no right to make it about me.

Years ago, when my column was hosted on a different

platform, it was understood that the terror victim beat was mine. I had a knack

for making people feel the horror, for making it real, for making the victim

real, someone the reader had never met. I had a knack for making women cry, reading my words.

And it began to feel icky, to feel exploitative. I didn’t

want to have thousands of pageviews only when I wrote about tragedy that

didn’t feel as though it rightly belonged to me. It was a writerly trick, no

more. I stopped. I didn’t want to do it anymore.

Plus, I have to say it affected me. I took it to heart. I

thought about the victims all the time. I dreamt of them. I carried them with

me. It hurt my heart. My heart. And finally my heart stopped. It had had

enough, had broken.

Hamas had, indeed, broken me. Broken my heart.

Several times a day I think about the hostages and the

victims of October 7, and my eyes well up with tears. “No! It’s not about YOU,”

I chide myself, though I know that this is my people and I too, own the sorrow

and the tragedy.

And yet something inside me feels guilty for imagining that

I know anything at all about what these people, MY people had suffered—even now

continue to suffer! I can picture it all in my writer’s mind. I’m a creative. I

picture everything in “living color,” the full horror of it all. I hear the

sounds, the flames, the screaming, I picture the baby. I can’t, I can’t.

***

In the ER, Elisheva sits by me as I go in and out of that strange brownout.

“How long is this going to take,” I ask her. “I need to get home to take care of

Dov.”

“You’re not going to be taking care of Dov, now.”

“But he just had surgery!” I moan.

“You’re not going to be caring for Dov. And you’re not going to

be cleaning for Pesach.

I continue to protest.

“Varda, this is serious,” she says.

Finally, I get it. Just as I finally understood that I had

to go in the ambulance—had to go to the hospital. I lie back. I accept it

for what it is. I died.

“You weren’t with us for a while,” says Elisheva, “You were

lucky you were awake when it happened.”

***

The day the war breaks out, I awaken to the noise of war. Booms.

Artillery. I know what I am hearing. My husband comes home from shul to tell me

what he knows. But he sees that I know and understand that we are at war.

Not that I did know or understand. I could not have imagined

the full horror of it all. No one could have imagined it except for the sick

minds of the black-souled terrorists who perpetrated deeds the Devil himself could

not imagine and would never have contemplated.

My youngest begins getting ready to go back to base. His

elder brother says, “What’s with all the panic? Slow down,” and I hear the

younger say, “You don’t understand!” and then whisper something about thousands

of terrorists on the loose, terrible things happening, terrible.

He gets ready to go, and as he’s going down the walk to his

car, the sirens go off and we make him come back in to go into the safe room. Finally,

he is able to leave with whatever food I can pack for him in a hurry.

Later, as the holiday comes to a close, the other son says

to me, “Don’t listen to the news. I’m telling you, Eema. Don’t listen to the

news.”

Telling me not to listen to the news is like telling me not

to breathe the air, not to drink water. I am all about the news. “Don’t do it,

Eema,” he says, my son, so wise beyond his years. “It’s not just the war on the

battlefield. There’s also the psychological war. They want to break us, Hamas.”

That stays with me. “Hamas wants to break us.”

I vow that Hamas will not break me. I say it to myself all day long—say it

until I am blue in the face. But invariably, I hear things on the news. I

cannot live under a rock. I need to know what is going on. And I hear terrible

things. Things that break me more and more.

Each time I chide myself. “How dare you make it about you? How dare you,” but I

can’t stop it from eating away at me. It nibbles at my heart, at the very core

of me.

Sometimes I listen to the testimonies of the survivors obsessively. I can’t

stop. I also cannot bear to hear them. “You’re not the only one,” I tell myself.

“Everyone in the country feels what you feel. Everyone. And the survivors have

it far worse—feel it far worse than you ever could”

But the hostages? How can I not feel this? The scenarios of

what is happening to them come to me unbidden. I can’t help it. I picture it

all. I picture it all. I cannot stop.

And it eats away at me, at my heart, until my heart said “ENOUGH,” and stops on

a strange dark morning.

I don’t really understand why, after it stops, my heart

once more begins to beat, except that God puts this instinct to live in all of

us. We live, sometimes with terrible knowledge, in spite of ourselves. Whether

or not we feel we can bear it all—all that life throws at us.

Later, in the hospital, the doctor comes to tell me that my

heart stopped for 30 seconds. He seems impressed by this number. My son who accompanies me to the hospital trades glances with me. We’d gone from the two

seconds cited by the MDA guy to 30.

That was in the ER.

Sometime after I am moved to the Intensive Care Cardiac

Unit, another doctor comes and says, “You had a ‘pause’ of 40 seconds.”

My son and I look at each other, both of us thinking, “First

two seconds, then 30 seconds, and now 40??”

The doctor nods. “Yes,” he says. “I counted it. There was a lot of ‘noise’ on

the EKG but I counted it myself and it was 40.”

We can see this is a long time from his perspective—that he

is impressed by this number.

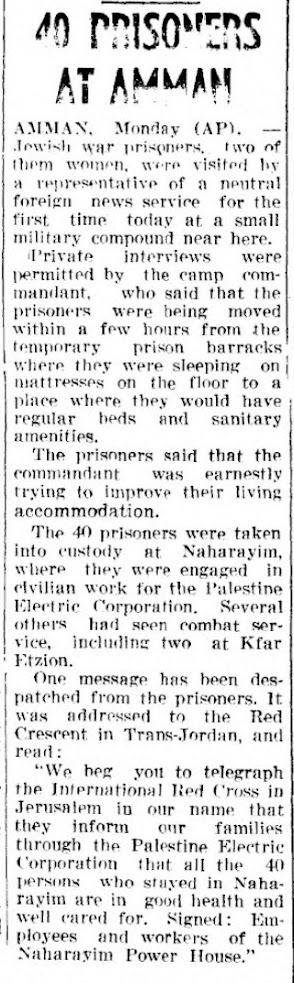

|

| Actual screenshot from my hospital release letter detailing the 40-second "pause." |

The next morning, the ward cardiologist comes to see me and he explains that there are pauses, long pauses, and very long pauses. Mine was apparently impressively long. “That is a LOOOOONG pause,” the white-haired physician tells me, adding that in his entire career, he had never seen such a long “pause.”

After many days and much testing—the tilt test, a shot of

atropine, an MRI—the doctors decide to put in a pacemaker. The local anesthetic

doesn’t work, and I scream as the knife slices into my flesh. “This is

nothing,” I tell myself on the table, “compared to what the hostages are

suffering, compared to what the victims of October 7 suffered.”

I am certain Hashem is giving me just the smallest taste of

what they felt/feel in their agony. Just the tiniest taste, so that I will have

some understanding, just a glimpse of what they went through, are still going

through. They deserve that, the victims and survivors. They deserve for us to

know and to feel it, too.

Our people, a part of us. A part of my own flesh, my own

blood, my own people, my nation. My heart. I hope that in some way, my

experience on the table will serve as a kapara against whatever sins had

brought this down upon our people. “This is my exchange, this is my substitute,

this is my atonement.”

Once home, I ask two cardiologist friends, “What’s the

longest ‘pause’ you’ve seen in a patient.”

One says, “Ten seconds,” the other says, “Ten, maybe 15 seconds.

Three seconds earns you a pacemaker, he adds.”

Neither one had seen a 40-second pause.

When I go back for my two-week checkup, the doctor squints

at me, trying to place me. I say, “I’m the one with the 40-second pause,” and

she remembers the case immediately, if not my face. What was my face to these

physicians? I was a “pause.”

The longest pause they had seen. I was a miracle: In spite

of Hamas, and almost in spite of myself, I lived.

Hamas broke me, but didn’t break me, because I lived.

My heart is not the same and there is lasting damage, yet I

live to tell the tale.

I live.

Because that is what the Jewish people do. We live

and outlive our enemies. And there is not a thing they can do about it. It’s

ordained by someone far more powerful than Hamas. And Hamas will come to know

this as the flames begin to lick at their feet for all eternity.

No one can best Hashem. No one. The Jewish people will dust

themselves off, never forgetting what has been done to them, and they/we will

continue to live.

Our God is more powerful than Hamas, than even the worst

that Hamas can do to us. The evil ones will never, ultimately, win.

As for me, my heart will never be the same, and that is only right. I am not stone, should not be stone when my/our people are suffering.

Now I know: it’s not that my heart betrayed me. I had to break, a

least a little. My injured heart proved to me that I am human, something that Hamas will never be.

Earlier: Part I: Varda wakes up, and begins to feel truly ill, and Part II: The medics arrive.

|

Or order from your favorite bookseller, using ISBN 9798985708424. Read all about it here! |

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)