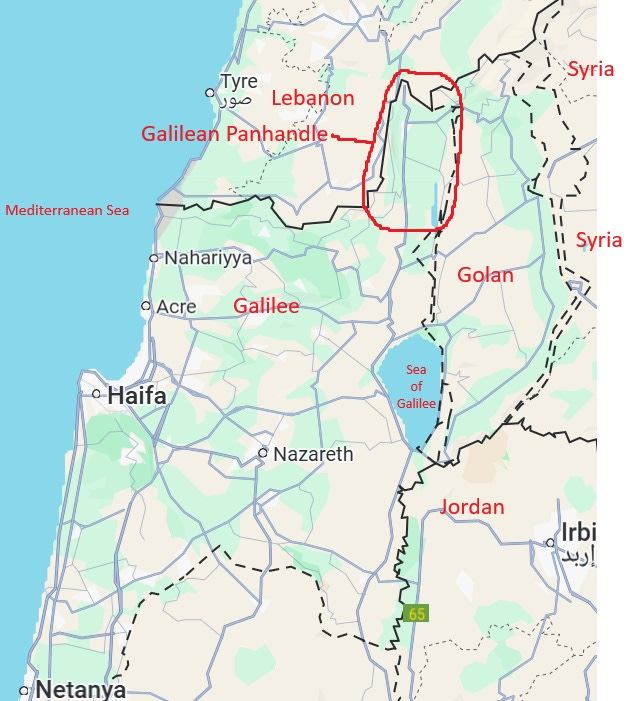

Highlights of a Visit to the War-Ravaged Galilean Panhandle

Unprovoked, Hezbollah attacked northern Israel on October 8, 2023, only 25 hours after Hamas initiated its invasion and atrocities of the farming villages of southern Israel the day before. Breaking the cease-fire that had been in effect for 18 years, Hezbollah had been firing guided antitank missiles at the northern Israeli border communities as well as longer-range rockets into the Galilee daily.

After more than a year of these attacks, a new cease-fire between Lebanon and Israel came into effect on November 27, 2024. Hezbollah’s firing of antitank missiles at Israeli border villages from southern Lebanon has finally ceased.

Taking advantage of this lull in hostilities, I joined a guided tour of the Galilean Panhandle Thursday, January 2, 2025. The purpose of this tour was to afford an opportunity to Israelis who don’t live in the border areas to see for themselves the extent of the damage to the border villages and towns, the toll on the population, and the early stages of rehabilitation.

First Stop–Kibbutz Manara

The village of the kibbutz is perched on the highest point of the mountain ridge that runs in a north-south direction along the Lebanese border (legally an armistice line). This point rises steeply 800 meters above and to the west of the Hula Valley.

Figure 1 Hula Valley from the Ridge Looking East, the Golan & Snow-Capped Mt. Hermon Opposite.

A Lebanese village, also perched on a mountaintop, is situated a few hundred meters to the west of Manara. The line of site from the Lebanese village to the houses on the kibbutz is unobstructed. This topography is ideal for Hezbollah fighters who live in the Lebanese village to fire laser-guided antitank missiles at their Israeli neighbors’ homes, and so they did 260 times during the war. Three-quarters of the houses were damaged to the point of being uninhabitable.

We were not allowed to enter the village itself because of the widespread destruction. We viewed it from a lower point from where we could see blown-out windows and rocket holes in the walls of the row of houses visible from there.

She recounted that within the first few days of the war all 260 inhabitants fled except for four who refused to leave. They fled not only because of the antitank missiles, but especially because of fear of an invasion, atrocities, and capturing of hostages such as were perpetrated on the farming villages of the Gaza Envelop in the south on October 7, 2023. Such a fear was well-founded because they knew that several thousand battled-hardened troops of Hezbollah’s Radwan Brigades were stationed just on the other side of the armistice line.

Confirming these fears were detailed plans and maps for such an invasion that were found in Hezbollah’s network of terror tunnels in South Lebanon adjacent to the border with Israel.1 Thankfully, that invasion didn’t materialize. But the threat of it was the impetus for evacuating 65000 residents of the northern border area from their homes in the first days of the war.

Another frightening finding in these tunnels was “astronomical quantities of weapons and ammunition...and they began to empty it out on us,” she said.2

A major consequence of the kibbutzniks’ fleeing was that there was no one left to work the orchards and vineyards. Making matters worse, any workers in them were sitting ducks. As a result they were able to harvest only 10% of their crops in the last year.

Regarding the future of the kibbutz, she lamented that it will take several years to bring the orchards and vineyards back into full production, and said, “We’re only at the beginning of the process of rehabilitation. It will take many months before people can begin to return to the kibbutz. I work every day with insurance assessors and tax authorities.”

The kibbutzniks and their families are now scattered all over the country. She and other responsible members of the kibbutz make sure to keep track of them all, where they are located, their welfare, any needs they may have, and any distress they might be in. Once every six weeks, they hold a kibbutz-wide meeting by Zoom in an effort to ensure cohesion among the members.

At a later stop in the tour, one of the guides commented that at the outbreak of the war there were 20 Gazan workers employed at Kibbutz Manara. The members of the kibbutz assigned the highest priority to ensuring that their workers got back home safely from Manara in the far north to Gaza in the south, by then engulfed in war, and they managed to do so.

Second Stop–Moshav Margaliot

Located a ten-minute drive north of Kibbutz Manara on the same ridge, Moshav Margaliot is a major domestic producer of eggs. Their chicken coops sustained extensive damage from antitank missiles.

Figure 2 Destroyed Chicken Coop

As opposed to a kibbutz, which is owned collectively, the families of a moshav each own their own houses and farms. This means that each family is responsible for rehabilitating its own house and agricultural infrastructure independently.

One of the moshav’s farmers spoke to us. Standing next to the border fence, he pointed out a Lebanese village on the other side situated on a higher ridge and separated from his moshav by only about 300 meters. From there, looking down on Margaliot is like “looking down at the palm of your hand,” he said. From the elevated position of the Lebanese village, Hezbollah repeatedly fired antitank missiles down onto Margaliot and all the houses were destroyed except for a few at the far end of the agricultural village.

He reported that during this war more cross-border tunnels penetrating into Israeli territory were discovered, including at Manara. Margaliot dealt with several attempts at infiltration. In one incident an armed terrorist managed to sneak into the moshav village. Guards pursued him but couldn’t find him until the next day when they shot him.

Our “additional war” is to restore the damaged agricultural infrastructure, the farmer explained. “Feed bins were destroyed. During the war mine was completely damaged but I repaired it because I still had poultry in the structure. The assessors said because you repaired it you don’t have to replace it, so no compensation for me even though it was already 20 years old. The others will get compensation to buy new ones prorated based on the remaining useful life before the war. A feed bin today costs ten thousand shekels. Repairing the structures themselves will cost 20 to 30 thousand shekels from your own pocket.”

He shuddered at the thought of what would have happened if three or four thousand battled-hardened troops from the Radwan Brigades had crossed the Lebanese border and in the twinkling of an eye covered the short distance to the small city of Kiryat Shmona in the valley below at the outbreak of the war.

Figure 3 Looking East Over the Hula Valley with Kiryat Shmona Below and the Golan Opposite

Looking ahead, he expressed uncertainty about “what would happen six months…, four years…, seven years into the future. So far between 20 and 30% of the residents have returned to the moshav. I estimate another 30 to 40% will return. 30% are estimated not to return. This is the moshav’s most pressing problem.”

The organizers had wanted to take us to Metula, the northernmost village in Israel on the Lebanese border. Before the war it was a popular tourist destination and hosted an annual Israeli poetry festival; during the war 300 of its houses were destroyed. The mayor refused to allow us to visit because he doesn’t want his village to be seen by outsiders in the devastated condition it’s now in.

Heading back to Tel Aviv, we stopped in the town of Kiryat Shmona in the Hula Valley. It was mostly empty, just like the southern town of Sderot was earlier in the war. From a bustling town it is now a ghost town.

Conclusions

During this war the northern communities were hard hit. Of the sixty-five thousand residents from the border communities that had to be evacuated to other parts of the country, so far few have returned because of a persistent perception of insecurity. The cease-fire now in effect is scheduled to expire at the end of this month. In any case, Hezbollah has been violating it since the first hours of its coming into effect by attempting to rearm by importing weapons and ammunition through Syria. The Lebanese army, assigned the role of enforcement, has been completely ineffectual so far, as predicted. So the IDF has had to stay in southern Lebanon to ensure compliance with the terms of the agreement. But the determination of the kibbutzniks and moshavniks, as conveyed to us by the representatives of the communities we visited, gives reassurance that the area will recover from the devastation and depopulation of the war, and will flourish again as long as security can be maintained.

|

"He's an Anti-Zionist Too!" cartoon book (December 2024) PROTOCOLS: Exposing Modern Antisemitism (February 2022) |

|

Buy

Buy